The Evolving Field of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) Chatbots

In this post, we’ll explore what generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots are and try to understand how we’ve gotten to this point in AI technology in general. To begin, I would like to acknowledge that the field of generative AI is growing and evolving rapidly. There is currently a lot of media coverage – not all of it accurate – on the topic.

Below, you will find key terms, an overview of questions about generative AI, and some initial information about how this technology developed and what you might watch out for when looking at generative AI tools. The goal is to give you an overview of this innovative field. Thank you to contributors, including James Yochem (Copyright Coordinator), Curtis Preiss (Manager, Cyber Security), and Cory Scurr (Manager, Academic Integrity).

Key terms

Chatbot – an app or interface designed to respond to text-based questions or prompts automatically and conversationally. These are currently often used in customer support.

Natural language processing (NLP) – The branch of AI researching and testing solutions around tools that learn from and replicate human-sounding language patterns.

Predictive analytics – using data sets of past patterns to guess what is likely to happen next.

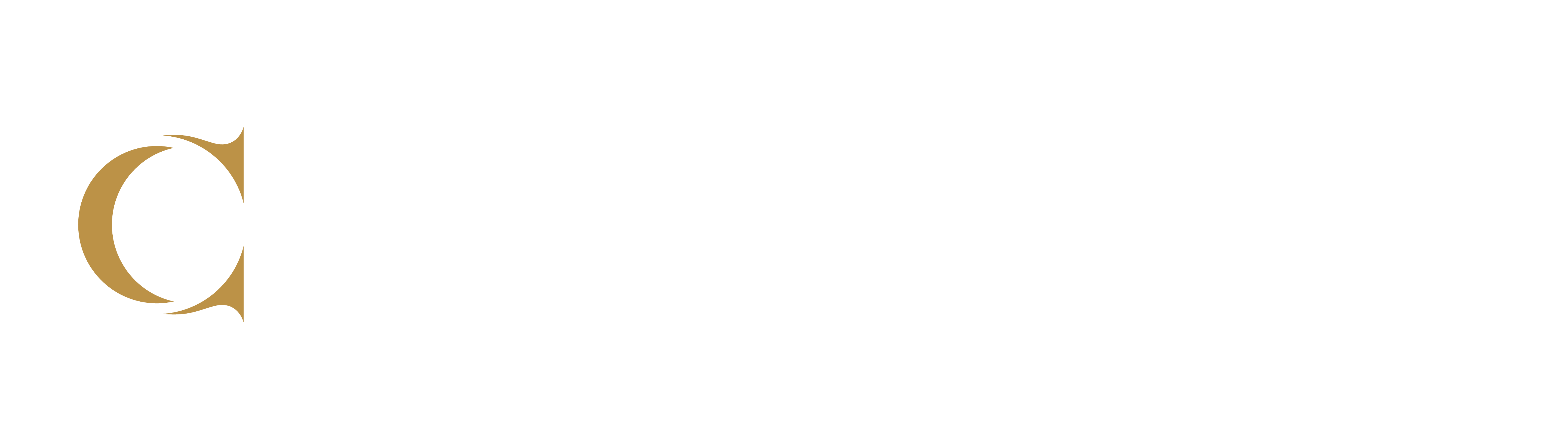

Artificial intelligence (AI) – A computer database, algorithm or program capable of performing activities that are normally thought to require intelligence, such as learning and reasoning.

Machine learning – a subset of AI – an algorithm designed to find patterns in sets of data and use these to make decisions. The dataset is typically already organized to support the effectiveness of the algorithm.

Deep learning – a subset of machine learning, an algorithm that can work better with unstructured data. The algorithm can determine from context the important information on which to focus, alleviating the requirement of human intervention to organize the dataset.

Large language models (LLMs) – an AI model that processes immense amounts of text (usually collected from publicly available online sources) and uses deep learning algorithms to detect and understand language patterns, common usages, and contexts. LLMs are uniquely capable of recognizing patterns of human communication and are typically enhanced through training by humans.

GPT-4 – generative pretrained transformer 4, an LLM created by OpenAI that uses deep learning to produce (generate) human-like text based on user prompts. GPT-4 can perform a range of related language tasks and is the third iteration of the service. It is uniquely able to do things it has not been explicitly trained to do.

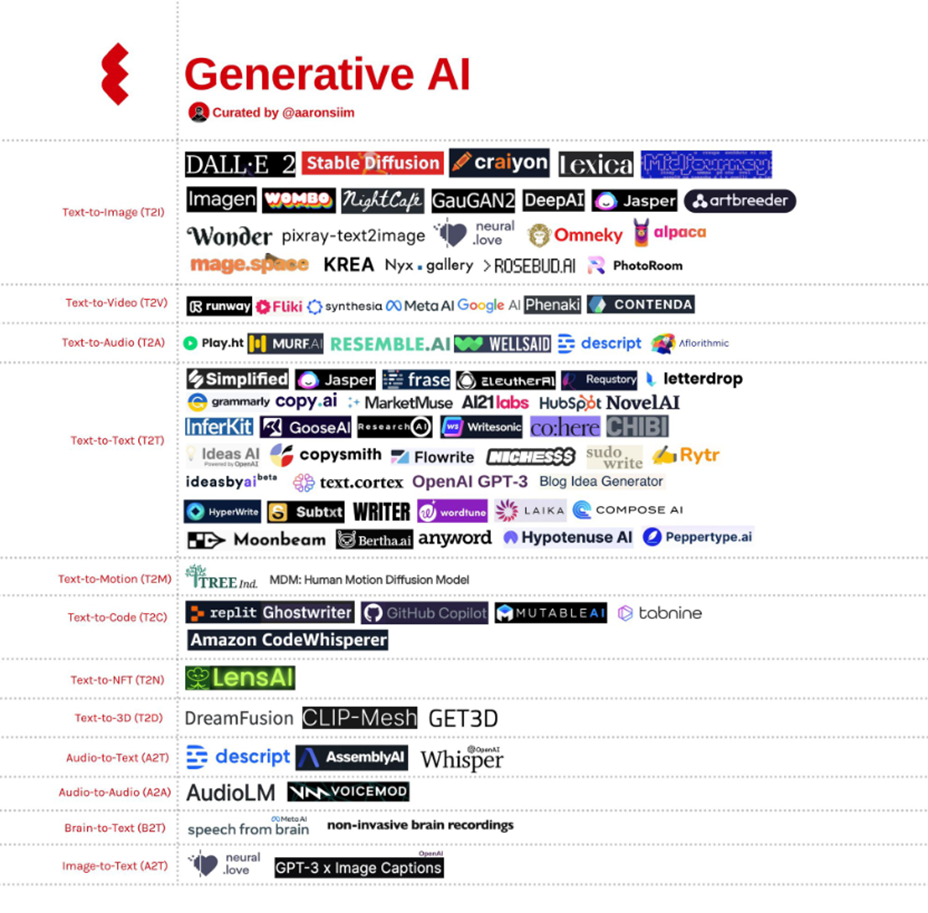

Generative AI – AI specifically developed to produce an output. These typically aim to produce text, audio, or video, but are expanding into other fields such as music as well. ChatGPT is an example of text-to-text generative AI, while tools like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2 are examples of text-to-image generative AI.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) – AI fully capable of human-like thinking and communication, including creative and original ideas and self-awareness (sentience). There are no current forms of AGI yet developed.

What is generative AI and how does it work?

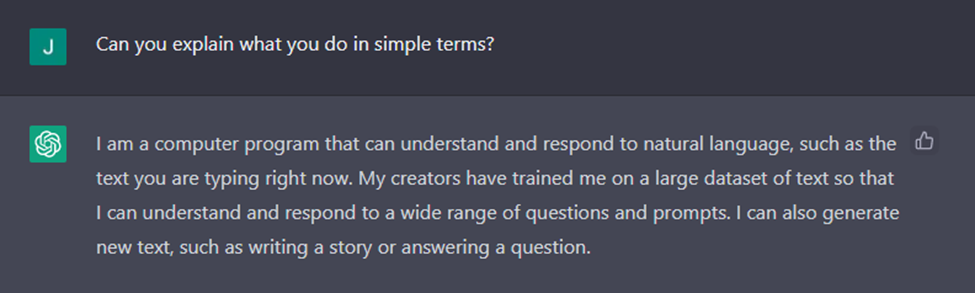

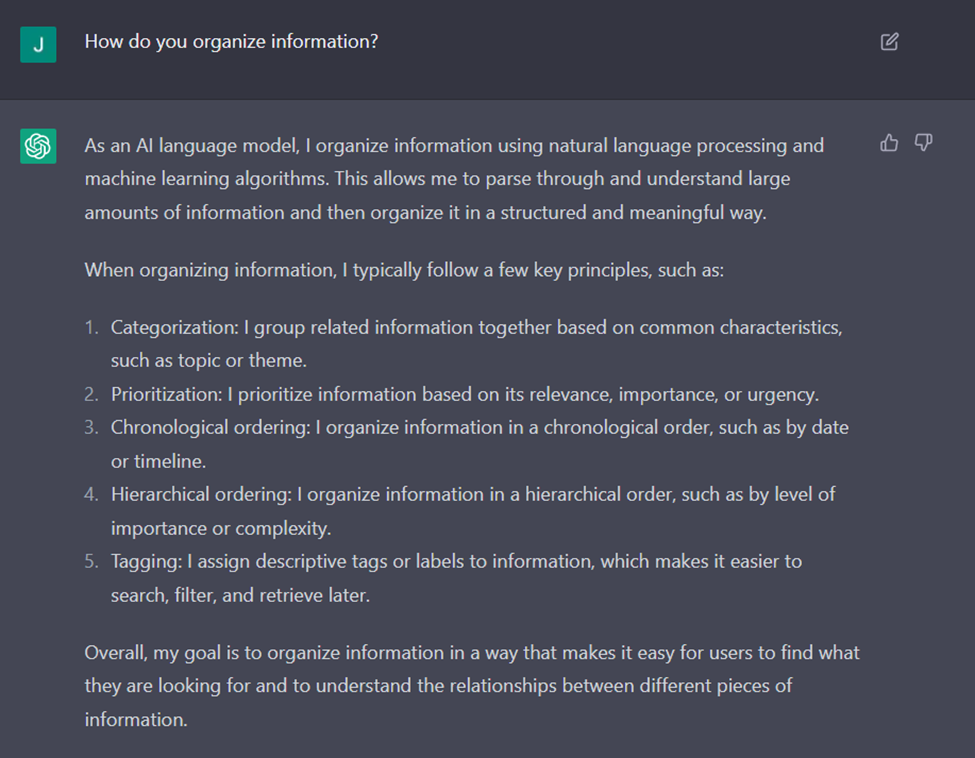

Generative AI often leverages chatbots, much like you might use to communicate with a website’s technical support, but more capable and powerful. You can ask a generative AI chatbot any question, and it will reply using everyday language (Figure 2). It replicates human writing and can write:

- essays or poetry in a particular style;

- process guides for accomplishing a task;

- working code,

- chemistry compositions,

- and a variety of text formats from a few simple user inputs.

Give a chatbot a few words or a sample lyric, and it can write you a song. Give it a few words of copy, and it can write a half-decent ad.

Figure 2: A prompt invites ChatGPT to explain its own capabilities.

In more technical terms, generative AI chatbots like ChatGPT are a front-end service designed to tap into a large language model (LLM). In the case of ChatGPT, it taps into GPT-4, the LLM released in 2023 by OpenAI. An LLM is a collection of billions of examples of text communications, typically scraped from information readily available on websites. Developers then layer in algorithms that help build predictions about what constitutes appropriate arrangements of text, sentences or paragraphs, or the recognition of patterns and common language forms and patterns. These algorithms use predictive analytics to calculate the suitability of word and content combinations (Devaney, 2022). Most major technology companies, such as Google, Facebook, Amazon and others, have their own LLMs.

The front-end chatbot, then, steps in and “fetches” information, presenting it to us in the familiar format of an online conversation. The chatbot also remembers questions and directives within the same conversation and uses these to continue adapting and refining its responses. The video below offers some additional details about how natural language processing works.

How did this technology develop?

Generative AI is not new and has been gaining momentum in recent years. Below, I have collected a timeline of notable advancements in AI since the 1940’s. It is by no means complete, but it is a look through the years of development that have led us to now.

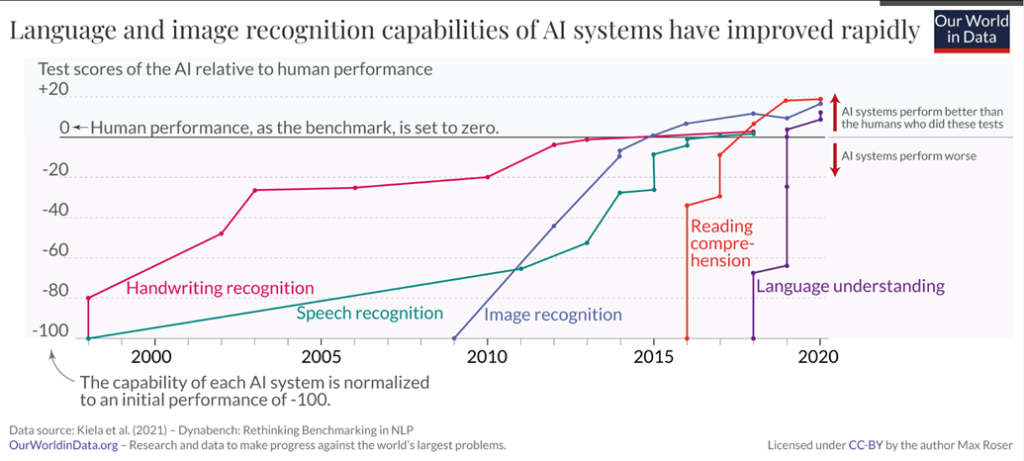

The development of LLMs is a byproduct of the branch of Artificial Intelligence research called natural language processing which seeks to replicate human language patterns and outputs. The language-based AI field has several key branches, each with their own trajectories of development. These key branches are primarily handwriting, image and speech recognition, reading comprehension, and language understanding (Kiela et al., 2021). Figure 7 outlines the rapid improvements in each of these AI branches, showing how quickly they have evolved to surpass human performance.

Figure 7: The rapid improvement of language and image-based AI systems.

Can I test out a generative AI chatbot?

You can currently use several generative AI tools, such as Bing Chat, CHatGPT, Perplexity, or YouChat at no cost. However, please know that some account creation processes may require two-factor authentication using a personal phone number. Please do not use your Conestoga email to create an account.

What are some other generative AI tools?

There are many different types of generative AI tools already available, which produce different forms of media. Many of these are paid services. A Canadian software engineer, Aaron Sim (@aaronsiim), posted a helpful visual (Figure 3) of some of the generative AI tools available (current as of 10/22, so already a bit outdated). This list shows us that generative AI can be used for many forms of media-to-media production, particularly generating text and images.

Figure 3: A non-comprehensive list of generative AI tools already on the market, typically as paid services.

You can also look into some of the alternative AI-backed apps and tools available, if you’d like to explore in greater depth.

What are the limitations of AI chatbots?

It’s important to keep in mind that the limitations of these tools are consistently evolving. One major limitation is that most LLMs are not capable of assigning importance or quality to different kinds of information, and treats misinformation and fact equally. They are also prone to a phenomenon called hallucination, wherein they construct responses that are not based in fact or reality. Hallucination will occur to some degree in all AI services based on LLMs. Many chatbots also might lack the capacity to accurately triangulate or synthesize from several sources, misattributing information to incorrect sources.

Additionally, many chatbots are unable to:

- Consistently associate correct details or characteristics with different characters, sources, or situations.

- Make predictions about the future.

- Summarize, attribute, or compare content accurately from multiple sources.

- Consistently follow prompts that contradict its own rules and restrictions.

These limitations should not be taken as faults or flaws. They are limitations reasonable to what these chatbots are designed to do – guess what words belong together in a particular context (Bender et al., 2021). We should keep in mind, however, that chatbots will likely continue to evolve quickly (Vincent, 2023).

Figure 4: A prompt asks ChatGPT to describe how it organizes information.

What should I know about who owns outputs from generative AI chatbots?

There are many uncertainties surrounding generative AI, but one of the most significant is copyright ownership. Who owns the input and output from these systems? Each chatbot will have its own terms of use, which will specify the ownership. In most cases, the company retains ownership of outputs.

For example, ChatGPT collects a record of all inputs and outputs used on the platform. (There is a conversation history that can be turned off.) The current terms and conditions of use establish OpenAI as the owner of any outputs, and they grant the end user (us) the rights to sell or redistribute that work. Similarly, OpenAI reserves the right to grant other people the right to also sell and redistribute the same or similar outputs. Some AI products, like Stable Diffusion, establish outputs as belonging to the public domain (CC0). This means you will not own the copyright on outputs you create using this chatbot.

Another concern is that LLMs are created using publicly available information scraped from the internet. This often includes copyrighted information, including publications, images, public domain content, websites, blogs and more. It is possible that outputs could produce a work that is a copy of a copyrighted work, particularly when it’s a highly culturally iconic work. For example, Stable Diffusion easily will produce near replicas of the Mona Lisa, due to its high prevalence in training data. A copy of a protected work like this could be considered copyright infringement.

Ownership of AI content will eventually be determined by a legislative amendment. Until ownership is determined by this amendment, it is not advisable to use ChatGPT in activities related to course materials production or assessment generation. Conestoga College’s Intellectual Property Policy clarifies that the college owns all material “developed by employees within the scope of their employment” (Conestoga College, 2018, p. 5). Using a system like ChatGPT could pass ownership of college intellectual property to outside interests. In addition, using output created by an AI system could put yourself and the college at risk of litigation if an output is considered a copy of another work.

Further questions can be referred to the Copyright Coordinator – James Yochem.

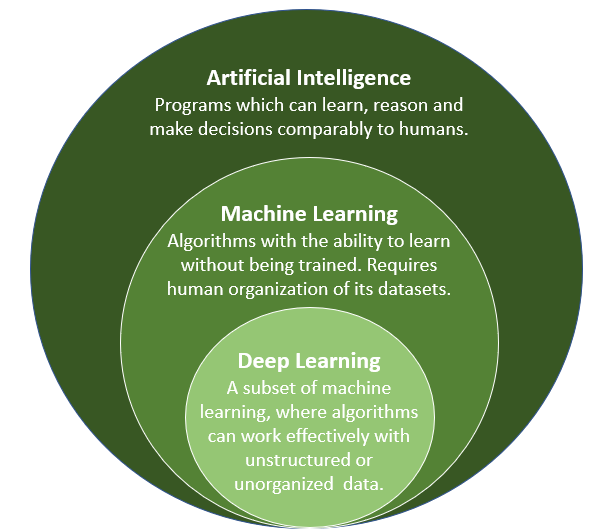

What data do chatbots collect?

Each chatbot will have their own data collection practices. They will also have their own levels of transparency around this. For example, in ChatGPT, users are reminded to be cautious of what they share within the service, and that there are human reviewers analyzing interactions. The data collected is used to shape the direction of future monetization and integration planning, and the information is shared with other organizations. In a preliminary review of the service, ChatGPT scored poorly against Conestoga’s privacy and cyber security standards.

Figure 5: Another of ChatGPT’s initial messages to new users informs them how they collect data.

As with any service if you are not paying for it, then you are the product. Paid services have agreements that may or not align with college recommendations and any exploration of these tools should be done in a controlled manner. It is currently recommended against using any of these tools in course development activities until the unknowns and agreements can be solidified.

Will AI content detectors be helpful?

Students may attempt to use AI-generated content as answers to prompts for assignments. While organizations like Turnitin, GPTZero, and OpenAI have released or proposed AI content detectors, their accuracy has not yet been adequately tested beyond the vendors’ claims, and there is little transparency about how their algorithms “detect” algorithmic writing outputs. On top of this, it is unclear whether AI content detectors will be consistently and reliably available or how they will retain and use the student-created works when input into their systems.

There is also evidence that AI content detectors can be easily evaded if suitable prompts are used. Students who create more sophisticated prompts may be more able to circumvent AI content detectors. Similarly, the students who are most likely to be caught using them are likely those who may be least successful in a course.

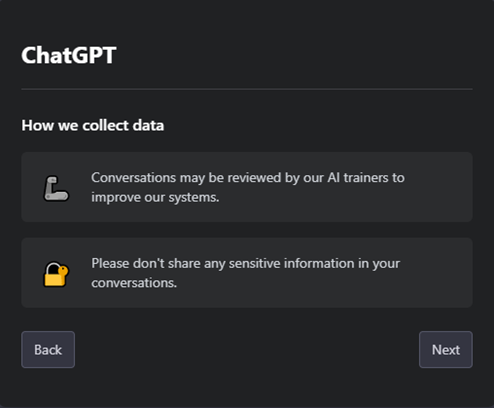

What risks should I consider when using generative AI chatbots in educational activities?

While it can be exciting and engaging to use an innovative tool like ChatGPT in teaching and learning activities, it should be remembered that LLMs have been criticized over several risks relating to privacy and reliability of information (Bender et al., 2021). It is recommended not to require students’ use of generative AI tools, and support choice and opting out if deciding to allow. Below, you’ll find some of the most notable areas of caution.

Figure 6: One of ChatGPT’s first messages to new users informs them of the intent of the service and the possibility of problematic or misleading outputs.

It may be inaccessible to some students, reinforcing existing digital divides in education.

Some students may be unable to pay for monthly fees for more sophisticated services, while other peers may be able to afford this. Consequently, there will be an imbalance in students’ access to quality generative AI tools. Microsoft’s AI-enabled Bing service is currently widely available but lesser known, and many other services also require payment. Generally, AI tools are likely to become more available, but we should keep in mind that paywalls will continue to limit public access.

It can be confidently inaccurate.

The writing tone and style of chatbots may sound confident, but they often present inaccurate information in a way that appears to be factual and sourced. This is a phenomenon known in AI development as hallucination. Chatbots may often fabricate references or quotes. Many services might do a poor job of accurately summarizing the information they have. This may improve over time but illustrates the importance of fact-checking and verifying information when presented. Service users will still need to evaluate the trustworthiness of any information generated.

They can be built on and produce harmful content.

LLMs are usually trained on publicly available information, like social media sites and public opinion forums. This means they are vulnerable to reflecting the biases, stereotypes, and bigotry exhibited in these spaces. Despite measures to train LLMs on appropriate responses and restrict inappropriate outputs, they can express bias, sexism, and racism towards different cultures or groups. They can also provide outputs with harmful potential, such as the code for potential malware. While tech companies have tried to implement barriers to malicious uses, these are not completely failsafe.

Students may develop cognitive overreliance on the service.

Learners may turn to generative AI chatbots as a solution to “looking it up” and begin to over-rely on these tools as sources of information. This may interfere with important mental processes of triangulation which occurs when we compare this source to others, gather our own inferences, and make conclusions (Zhao, 2023). Enhancing teaching and learning activities that prioritize thinking processes of analysis, comparison, or synthesis may help support this problem.

Where might this go next?

The release of ChatGPT has spurred significant movement from both collaborators and competitors. Microsoft has already incorporated GPT-3 into Azure and incorporated elements into Word, Outlook, and Bing to increase its competition with Google. It was already integrated in 2022 into GitHub Copilot, a coding production service (and another Microsoft product). Soon, we’ll also see the release of Microsoft Designer, an alternative to design tools like Canva and Visme. We can also expect other tools to develop using the GPT-3 (or GPT-4) protocol, as OpenAI offers subscription-based API access, allowing developers to create apps using the LLM as a backbone.

Over the next several years, we will see our search behaviors augmented with chatbot interactions. Google, Amazon, and other large tech organizations have all released similar managed-development platforms for their LLMs over the past three years (see the timeline in How did the technology develop? for details). Google has released consumer-level AI tools, including a chatbot named Bard (Milmo, 2023). Facebook released a similar chatbot a few months prior to ChatGPT. AI chatbot growth is also international – for example, Baidu in China is rapidly moving forward with the release of Ernie (Yang, 2023). Considering the initial steps being taken, these tools will likely have a significant impact, particularly on how we use search engines to find information.

Businesses will begin to look to incorporate these tools into services or processes. Many industries, such as healthcare, agriculture, insurance, food production, and customer service, already have forms of AI built into systems that could be enhanced or complemented with what LLMs offer (Wallis and Mac, 2018). The rapidly changing field of AI will likely be a prominent element of research and development projects for both businesses and research initiatives over the coming years.

How can I learn more?

Consider attending some of the workshops available from Teaching and Learning on generative AI.

If you’re looking for additional context on how AI is developing in Canada and what it may look like in various industries, The AI Effect is a two-season podcast investigating “themes around the Canadian AI ecosystem”. (Found on Apple, Spotify, or any other major podcast platform.)

The Université de Montreal has established the Montreal Artificial Intelligence Ethics Institute (MAIEI), which has established the Montreal Declaration of Responsible AI, which offers ten guiding principles to lead AI development.

Generative AI services and technologies are developing rapidly. This information is being updated regularly but may be outdated depending on its most recent update. Check back often for new information, or try one of our other Generative AI articles for more information.

Works Consulted

Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Bishop, T. (2023). ChatGPT coming to Azure: New integration shows how Microsoft will leverage OpenAI partnership. Geekwire.

Conestoga College. (2018). Intellectual property policy.

Darlin, K. (2022). ChatGPT: A Scientist explains the hidden genius and pitfalls of OpenAI’s chatbot. BBC Science Focus, December 14, 2022.

Devaney, P. (2022). What is the Difference between ChatGPT and GPT-3? gHacks.net (December 30, 2022).

Hao, K. (2020). The messy, secretive reality behind OpenAI’s bid to save the world. MIT Technology Review, Feb. 17, 2020.

Kiran, S. (2023). Microsoft in Talks to acquire a 49% stake in ChatGPT owner OpenAI. Watcher.Guru.

Kiela, D., Bartolo, M., Nie, Y., Kaushik, D., Geiger, A., Wu, Z., Vidgen, B., Prasad, G., Singh, A., Ringshia, P., Thrush, T., Reidel, S., Waseem, Z., Stenetorp, P., Jia, R., Bansal, M., Potts, C., Wiliams, A. (2021). Dynabench: Rethinking Benchmarking in NLP. Computer Science, arXiv:2104.14337

Kraft, A. (2016). Microsoft shuts down AI chatbot after it turned into a Nazi. CBS News, March 25, 2016.

Loizos, C. (2023). That Microsoft deal isn’t exclusive, video is coming and more from OpenAI CEO Sam Altman. TechCrunch.

Loizos, C. (2023). Strictly VC in conversation with Sam Altman, Part Two (OpenAI). [Video].

Maruf, R. (2022). Google fires engineer who contends its AI technology was sentient. CNN Business, July 25, 2022.

Milmo, D. (2023). Google AI Chatbot Bard sends shares plummeting after it gives wrong answer. The Guardian, February 9, 2023.

Nellis, S. (2019). Microsoft to invest $1billion in OpenAI. Reuters.

OpenAI. (2018). OpenAI Charter.

OpenAI. (2019). Microsoft Invests in and Partners with OpenAI to Support Us Building Beneficial AGI. [Website].

Peldon, S. (2022). Who Owns ChatGPT? Everything about the chatbot’s Microsoft-backed developer. OkayBliss, Dec 29, 2022.

Strubell, E., Ganesh, A., McCallum, A. (2019). Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP. MIT Technology Review.

Tamkin, A., Brundage, M., Clark, J., Ganguli, D. (2021). Understanding the Capabilities, Limitations, and Societal Impact of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.02503.

Tamkin, A., & Ganguli, D. (2021). How Large Language Models will Transform Science, Society and AI. Stanford University Human Centered Artificial Intelligence.

Vincent, J. (2023). OpenAI CEO Sam Altman on GPT 4: “People are begging to be disappointed, and they will be.” The Verge, January 18, 2023.

Wallis, J. and Mac, A. (2018). The AI Effect: Industry Adoption. [Podcast].

Yang, Z. (2023). Inside the ChatGPT race in China. MIT Technology Review February 15, 2023.

Zhao, W. (2023). AI Talks: The AI Tsunami – Where Will it Take Us? [Panel Discussion]. University of Waterloo, January 24, 2023.