Transitioning to a Digital Text

Research shows tremendous advantages to using study tools built into most e-reading tools. Several researchers have been able to associate greater use of study tools with improved outcomes achievement as measured by final assessments (Junco & Clem, 2015; Van Horne, Henze, Schuh et al., 2017).

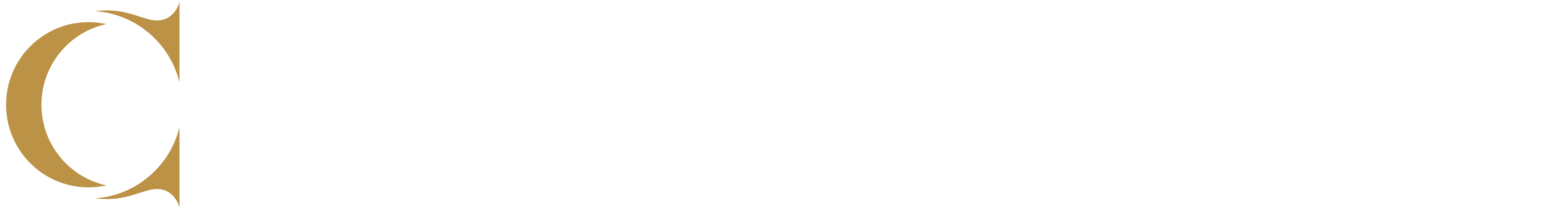

Know the Features

The first factor to consider when teaching with digital texts is your own comfort with studying with them. Educators can be the most influential factors in learners’ success with digital texts, and how you use the text will mentor how learners use it (Graydon, Urbach and Kohen, 2011).

Features can differ depending on whether you teach with an eText, an Open Education Resource (OER), or a digital platform. As a general rule, assume that if it can be done with a print book, it can likely be done with a digital one. Explore using the digital text on both a laptop and a smartphone.

Remember that eReader apps and platforms should be very similar but vary. It is this variation in eReader apps that poses the most challenge to learners in using and reading digital texts (Gu et al. 2015; Knight 2015). Testing them out is often the best way to find their strengths and boundaries.

Pre-Assess Learners’ Familiarity

Pre-assessing learners’ familiarity with digital texts before teaching can give you a realistic picture of how to support learners’ use of them (Van Horne, Henze, Schuh et al., 2017). Use a polling or survey app to determine how comfortable or familiar learners are with reading digital texts. Send this out before the first class, or incorporate it into your first lesson.

Ask learners to rate their own skill or comfort level with criteria related to digital reading. Some questions that might help you understand their needs could be:

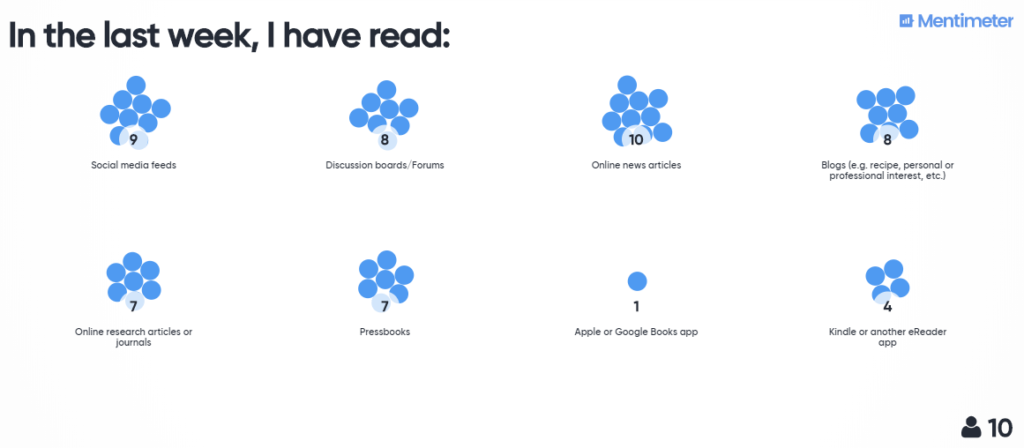

- “In the past week, I have read…” where students select from various types of informal and formal digital reading, like social media feeds, news articles, blogs, academic journals, Pressbooks, eReader apps, or Texidium.

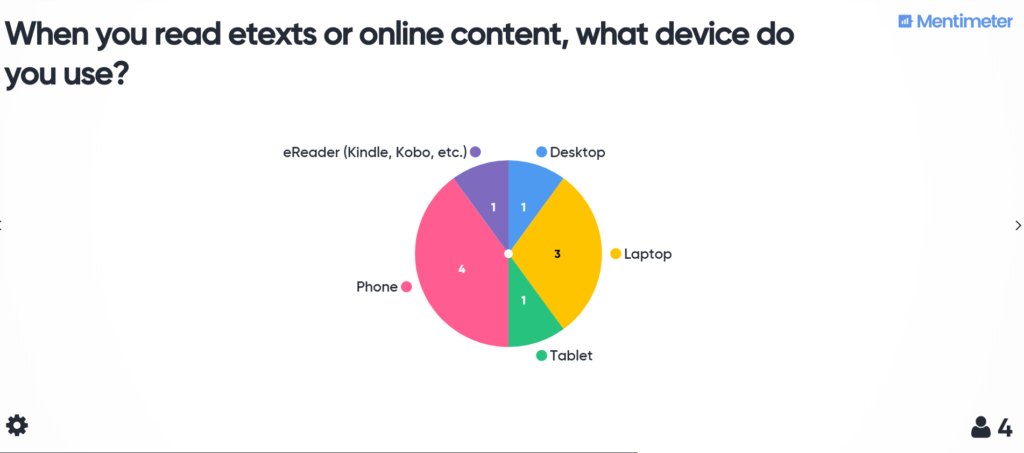

- “When you read this online content, what device do you usually use?” where students choose from a desktop, laptop, eReader, tablet or phone.

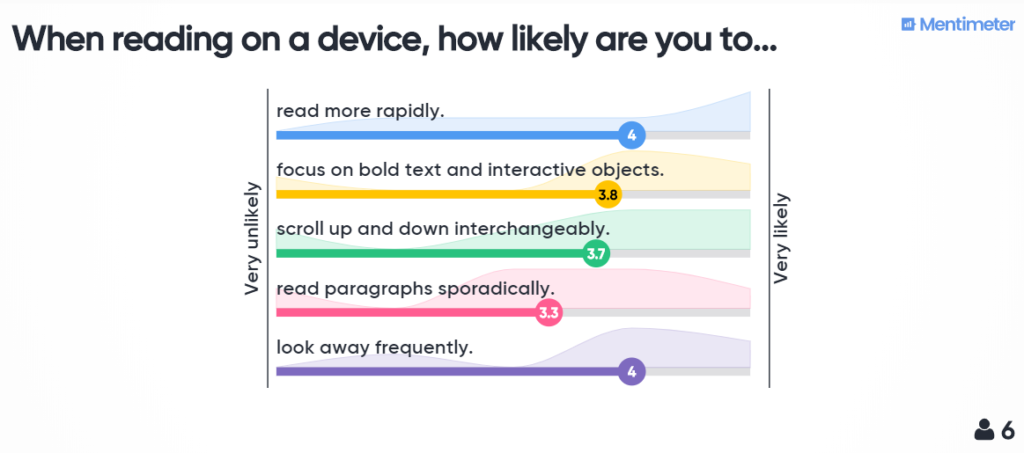

- “When reading on a device how likely are you to…” and provide a selection of features or behaviours that people might rely on. Encourage students to self-reflect on their reading behaviours or comfort level with reading digital books.

The answers to these questions will help you determine how much experience learners have with digital texts, and whether learners will benefit most from instruction prompting them through the laptop or mobile reading experiences.

Offer Time to Explore

Many students may be brand new to studying with a digital text, particularly if they are international students. Providing information or coaching on the best ways to use digital texts also creates higher satisfaction about their value (Van Horne, Henze, Schuh et al., 2017).

Especially in the first semester of the program’s first year, give learners an orientation to their new reading environment. You might try supports like:

- A short screen recording explaining how to access their digital text before class;

- Co-creating a list or word cloud of study tools they use most frequently (e.g. highlighters, sticky notes, table of contents);

- A time-limited opportunity to explore the text, finding each of these tools (or a variation);

- A guiding question prompting learners to find features that extend their usual studying habits (e.g. search, linking, sharing highlights, text to speech);

- Clear explanations of how the text will be incorporated into classroom learning;

- Encouragement that effective studying with the text will help their course and program learning.

Incorporate it into the Class

Although showing students how to use digital texts can help create higher student satisfaction, it will not guarantee their effective use. Remember, digital reading is much different than paper reading. Instead, the text needs to be deeply incorporated into classroom learning experiences (Van Horne, Henze, Schuh et al., 2017).

Some opportunities to incorporate the text into class activities include:

- Showing the digital text on the projector during appropriate activities or exercises.

- Creating an example chapter with highlights and notes and sharing this to students.

- Using read-aloud features to model new vocabulary;

- Have students share chapter highlights with each other, and compare their notes, creating a list of key commonalities.

- Do a think-pair-share in class about the benefits and challenges of studying from the text and how they can work within the challenges;

- Build study materials by asking learners to extract their highlights and notes and rephrase or summarize these continuously.

Prepare for Mistakes

Caution students about ways a digital text can be misused. A digital text can become disorganized the same way a paper one can, if no guiding principles exist to help structure studying. Common mistakes readers make include:

- highlighting too much of the chapter;

- under-using sticky notes;

- ignoring the search and table of contents;

- inconsistent colour coding;

- copying and pasting directly into study notes without summarizing.

Many of these can be managed by co-creating studying habits, and having learners regularly organize, share and compare notes. These can also act as co-teaching opportunities, where learners support each other in using effective studying and troubleshooting tips with digital texts.

Support Choice

Learners benefit from flexibility, which also goes for their digital texts. Many learners identify that their greatest challenges with a digital text center around consistent access (Mizrachi, 2015). Some factors that influence this are

- Their access to laptop devices;

- Their general computer skills;

- Their access to internet at home.

There are a lot of ways to work within these challenges. Some suggestions include encouraging learners to

- access the text through an app or browser on their phone;

- make sure their text is downloaded and available offline.

Improving flexibility of access helps learners to see that their digital text is available anytime, anywhere, and avoids some of the challenges of equity and access.

References

Graydon, B., Urbach, B., and Kohen, C. (2011). A study of four textbook distribution models. Educause Review, Thursday Devember 15, 2011. Retrieved November 13th, 2019 from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2011/12/a-study-of-four-textbook-distribution-models.

Junco, R., Clem, C. (2015). Predicting course outcomes with digital textbook usage data. The Internet and Higher Education, 27(October), 54-63.

Mizrachi, D. (2015). Undergraduates’ Academic Reading Format Preferences and Behaviors. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 301-311.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.009.

Van Horne, S., Henze, M., Schuh, K.L. et al. (2017). Facilitating adoption of an interactive e-textbook among university studenst in a large, introductory biology course. Journal of Computers in Higher Education 29(477).