How We Read Digital Texts

Many people make the mistake of thinking of digital texts as simple substitutions for physical ones. But research indicates we read fundamentally differently online than we do on paper (Delgado et al., 2018; Kong, Seo, & Zhai, 2018). Over the past 20 years, researchers have investigated a variety of reasons why this might be the case. The following points intend to expand on the different reading behaviours learners use when reading digital texts, and how this affects their reading comprehension.

Reading to Navigate

There are two key behaviour sets that readers engage in to read digitally: reading to navigate, and navigating to read (Murray & MacPherson, 2006).

Reading to navigate is how readers figure out how to move through the reading environment. Just as we consult the legend in a map before reading, readers first seek to orient themselves to a digital text. Many readers have likely not formally read a digital text with any frequency or consistency in the past, and so this consumes some cognitive effort.

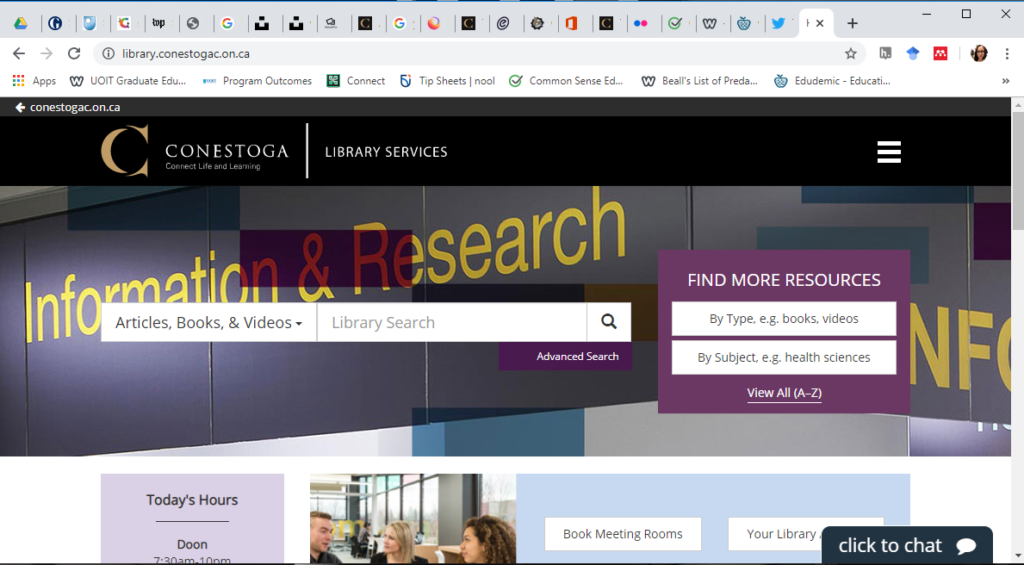

Readers spend time figuring out menus, layout and click options before they engage with text. Often, every new text or web page is completely different, which further slows down reading. Unless the reading environment is very simple, readers may need support in orienting to a new reading experience.

Navigating to Read

Navigating to read is how readers move through the text to find the information they need. An example of this is F-pattern reading (sometimes also called Z-pattern reading). Since the late 1990’s, researchers have used heat mapping and eye tracking to collect data about navigating reading online (Neilsen, 1997). This heat mapping shows that a person reads across the first major heading, then skips down to read across the next major heading, looking to quickly determine where the relevant information is. This behaviour happens in inverted format for languages reading right-to-left, making it cross-cultural (Pernice, 2017).

This reading strategy helps a person read efficiently, but it doesn’t lead readers to absorb all of the written content. Pages with large blocks of written content may go largely unread unless learning activities prompt readers to read in-depth.

Scanning and Skimming

Scanning and skimming are also well documented digital reading behaviours associated with navigating to read. Readers scan a page, looking for bolded text, hyperlinks, key words and numbers, in search of relevant passages to read (Duggan & Payne, 2011). They then skim these passages, looking for sentences that directly answer key questions, rather than reading whole paragraphs. This is much the same as flipping through a book, except digital readers do this almost all of the time.

Scanning and skimming is almost automatic in digital reading and likely contributes to observations that show shallower reading behaviours with digital texts.

Eye Strain Conservation

Readers of digital texts innately practice eye strain conservation by reducing the volume of text they read to just 20% of what is presented (Neilsen, 1997). F-shaped pattern reading, scanning, skimming, and page navigation strategies all serve the purpose of conserving eye strain. Reading on backlit screens can be taxing. Blue light and strong light sources are factors in depreciating eye health, sleep issues and mental fatigue.

To help reduce eye strain, readers also look away frequently, meaning their attention is broken more often. This broken attention might lead into the next behaviour typical of digital reading, multi-tasking.

Multi-Tasking

Multi-tasking feels productive, but is actually distracting. Digital readers, especially on laptops or computers, are frequently engaged in multiple activities and are prone to distraction from notifications and tempting clickable buttons.

Screenshot by J. Wilkinson, December 11th, 2019.

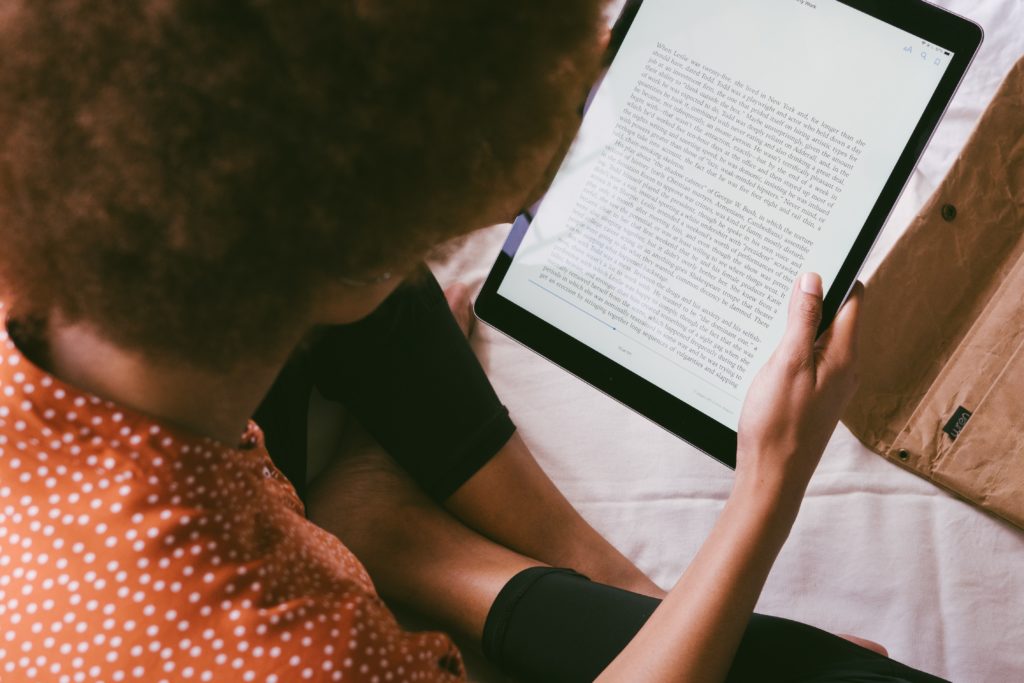

Interestingly, multi-tasking and shallow reading are less likely to occur when reading on smartphones or tablets (Delgado, Vargas, Ackerman & Salmeron, 2018). Separating reading devices (mobile phones and tablets) from working devices (laptops or computers) seems to positively influence multi-tasking behaviours.

Self-Regulation

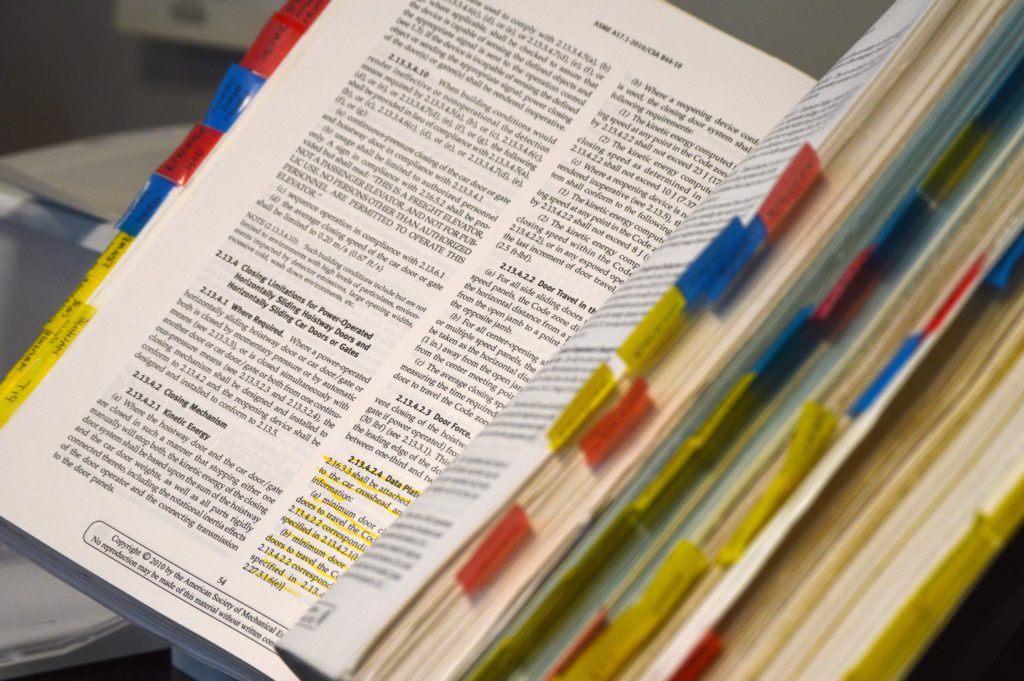

Related to multi-tasking, self-regulation is the capacity to monitor one’s own learning. With paper books, we do this almost automatically, by thinking about our purpose for reading, and using sticky notes, page annotations and tabs to keep us on track and address this purpose. But we often don’t leverage these types of strategies when reading digitally.

To add to the problem, we are overconfident in our digital reading habits, which makes us even less likely to self-regulate (Ackerman & Goldsmith, 2011). This overconfidence is only beneficial to those who prefer digital reading to print – for readers who prefer print, it results in a significant loss in comprehension.

Preference

Many cultures have strong historical and emotional ties to reading. Many people associate reading with leisure, pleasure and comfort, immersing ourselves in narratives or new learning. Readers also love the concreteness of a marked up text, one with lots of tabs and annotations and sticky notes to remind us how far we’ve come.

Yet readers don’t associate these same feelings of attachment or physicality with reading digital texts. The most frequently selected benefit of digital reading is simply convenience, not preference or enjoyment. Without this last affective connection to tie readers to their task, its becomes difficult to sustain attention and motivation to complete a reading deeply.

Tips

As you can imagine, these reading habits impact the degree to which a learner absorbs and retains information. There are some key strategies that can be implemented in class to support this, however.

- Orient learners to the reading experience.

- Demonstrate, or ask them to discuss with a peer, how they can use highlighters and sticky notes through browser extensions or in e-reading apps.

- Reduce the quantity of reading you expect learners to accomplish – typically extractions between 1000 and 2000 words are long enough.

- Ask learners to re-read sections in class for discussions or activities.

- Ask learners to re-highlight sections, identifying only the most important sentences or points.

- Have them summarize in their own words, and compare the summaries among peers, identifying key commonalities.

- Encourage them to use something like a QQC journal, where they collect their questions, quotes and comments in an ongoing, reflective way.

- Encourage the use of night or dark modes, which invert colours to give a black screen and white text and conserve eye strain.

- Incorporate metacognitive reading strategies into lessons.

References

Ackerman, R. and Goldsmith, M. (2011). Meta-cognitive regulation of text learning: On screen versus on paper. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17 (1), pp. 18-32.

Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R., Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: A meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educational Research Review, 25. 23-38. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.003.

Dobler, E. (2015). E-Textbooks: A Personalized Learning Experience or a Digital Distraction? Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58(6), 482-491. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/44009184.

Geoffrey B. Duggan and Stephen J. Payne. 2011. Skim reading by satisficing: evidence from eye tracking. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’11). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1141-1150. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979114.

Junco, R., Clem, C. (2015) Predicting course outcomes with digital textbook usage data. The Internet and Higher Education 27(October), 54-63.

Kong,Y., Seo, Y.S., Zhai, L., (2018). Comparison of reading performance on screen and on paper: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 123, 138-149. DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.005.

Lauterman, T., and Ackerman, R. (2014). Overcoming screen inferiority in learning and calibration. Computers in Human Behavior, 35. 455-463. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.046.

Murray, D. E., & McPherson, P. (2006). Scaffolding instruction for reading the Web. Language Teaching Research, 10(2), 131-156. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168806lr189oa

Neilsen, J. (1997). How Users Read on the Web. Neilsen Norman Group, September 30th, 1997.

Pernice, Kara. (2017). F Shaped Pattern of Reading on the Web: Misunderstood, But Still Relevant (Even on Mobile). Neilsen Norman Group, November 12, 2017.

Van Horne, S., Henze, M., Schuh, K.L. et al. (2017). Facilitating adoption of an interactive e-textbook among university students in a large, introductory biology course. Journal of Computers in Higher Education 29(477).

2 Responses