Concept and Mind Mapping

What is it?

Concept and mind mapping are graphical ways to represent knowledge, concepts and ideas. The maps are hierarchical in nature that expands on a core concept or question one idea or item at a time. Each idea or item can be a word, phrase, image, link or resource that helps define different aspects of that core concept. Common applications in education include summarizing, brainstorming, note taking, planning, organizing research, and studying. Research shows that mapping is an effective and efficient educational practice that helps all learners see and make connections between what they know and what they’re learning [1][2][3][4].

Concept Maps vs. Mind Maps

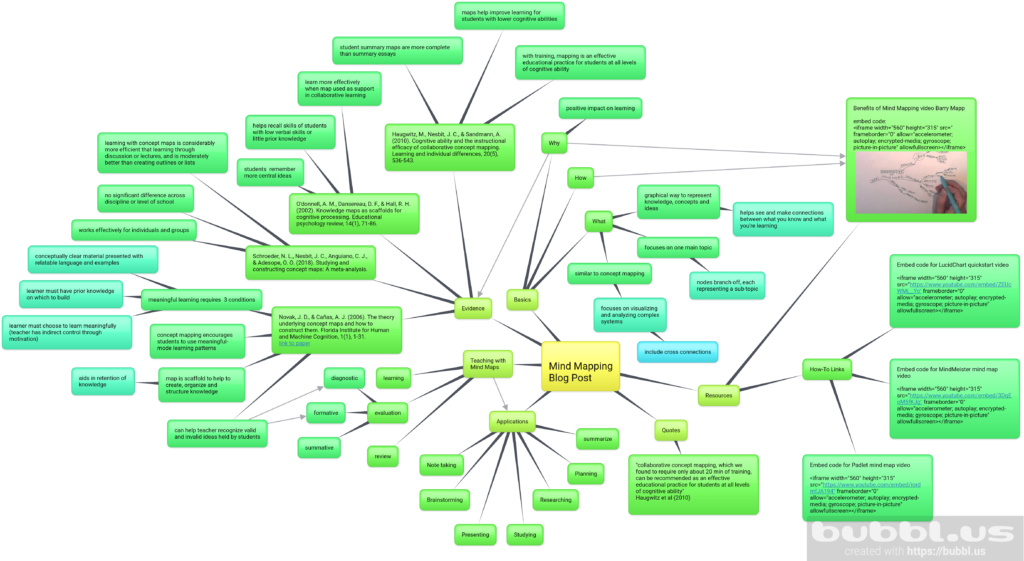

Most people use the term concept map and mind map interchangeably, but there are subtle differences between the two types of maps. A mind map is a tool that focuses on one key topic or concept. It starts with a central question or topic with sub-topics or nodes branching off this central point. The map can have as many sub-topics and levels as your thinking allows. Some mind map advocates recommend using a single word or image on each branch, while others put as much information in a node as they need to remember.

Concept maps are usually associated with complex systems. They are often made up of a series of interconnected maps that together define the system. In education they are often used to establish the properties of and relationships between particular aspects of discipline-specific knowledge or processes.

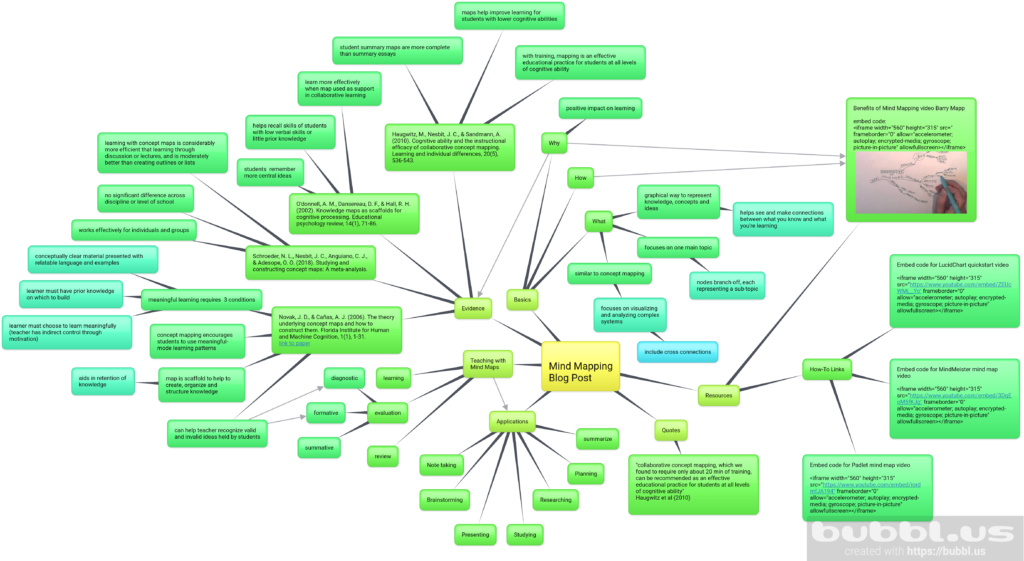

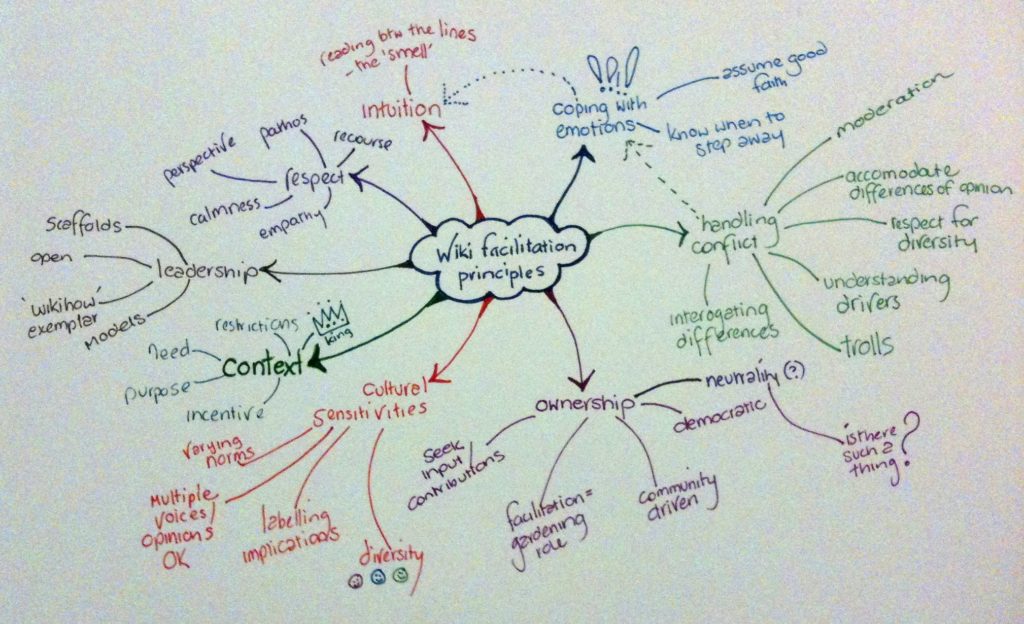

Many people (including me) use a combination of mind mapping and concept mapping techniques. Here, for example, is a mind map I used to plan for this blog post. The core idea is the yellow node in the middle. It has branches to six nodes: (1) basics, (2) evidence, (3) teaching with mind maps, (4) applications, (5) quotes, and (6) resources. Each of those nodes has a number of sub-nodes, and some of those have their own sub-nodes. Notice that some of the nodes are linked to multiple nodes. This shows that, even though these nodes are each part of separate branches, there are interconnections between them.

What makes concept and mind mapping so effective for learning?

We know that there is a difference between memorizing and actually learning new content. Concept mapping has been shown to help support deep (rather than rote or surface) learning [2]. Other researchers find that concept maps help establish and revisit prior knowledge, and organize and collect new knowledge into meaningful structures. They help learners find patterns across learning units, enabling them to make connections between new information and their existing knowledge [3].

The simplicity and structure of mind maps can help reduce students’ cognitive load (the demand placed on working memory while learning) [1]. Using mind maps can also benefit learners who may have minimal prior learning or who may have challenges processing language [3]. The highly visual and interactive nature of mind maps helps learners explore and recall structures, examples and concepts.

Uses

Mind maps can be used to both support and assess student learning. The opportunities include (but are not limited to):

- a beginning-of-class review or pre-assessment that has students individually or collaboratively create a map of the concepts covered in the last class(es)

- a mid-class exercise where the teacher guides students in the creation of a map that helps consolidate and link new concepts to ones previously learned

- an end-of-class or post-assessment where students create and either submit or peer evaluate maps of what they’ve learned in this class (this can also make visible any misconceptions students may have)

- an end-of-unit or pre-exam review where students collaboratively create maps that summarize key concepts

- brainstorming ideas related to designs, problems, challenges, etc.

- planning a research paper or essay

Process

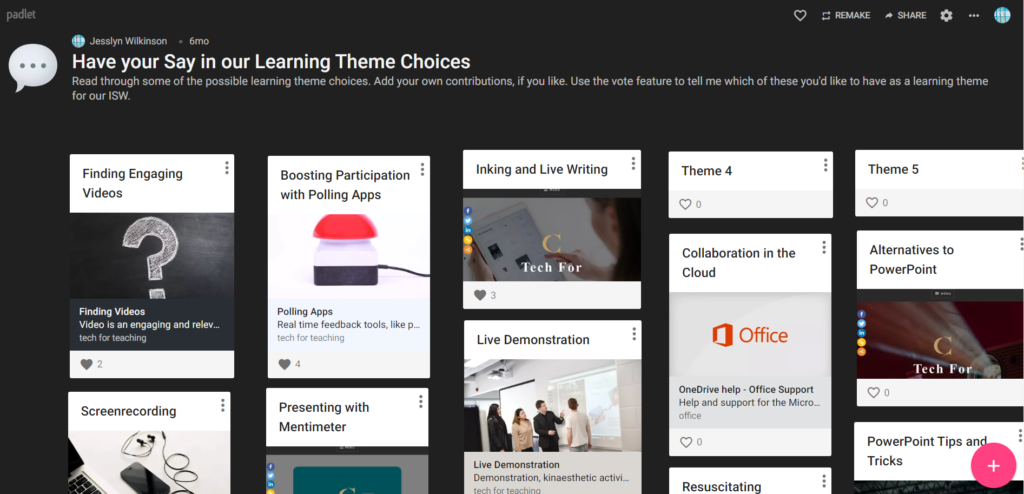

Ideas take many forms and so should concept maps. Whether you ask learners to concept map with markers and paper, whiteboards, or an app like Padlet, assume learners will want to incorporate variety. Concept mapping apps are often collaborative and allow for sharing and re-editing, making them more flexible and valuable for learning.

Provide instruction on your expectations for any map. Research shows that students can create a mind or concept map with 20 minutes of instruction [1]. Explain to students what a mind map is, show them some different examples, and then model how to build one. Make sure you demonstrate and provide instructions for any apps or software that you want the students to use.

Concept mapping should not rely on text alone but allow users to incorporate images and other common resources such as video, audio, links, and embeds. Ideally, learners should be able to revisit, reorganize and – most importantly – share their maps with peers. In some cases you may want a mapping app that incorporates interactive activities such as liking, commenting and up-voting each others’ contributions.

Adapting to Different Modes

| Delivery Mode | Adaptations |

|---|---|

| In-Person | Provide a clear whiteboard space and whiteboard markers, or suggest a digital whiteboard app. Leave the activity flexible enough so that learners can choose either a digital or analogue (paper and pen) option to match their skills and comfort level. Provide the chance for everyone to show and share their maps. |

| Synchronous Online | Suggest a digital whiteboard app or use a concept mapping app. Make sure to scaffold learners use, as learners may be new to this kind of tool. Leave the activity flexible enough so that learners can choose either a digital or analogue (paper and pen) option to match their skills and comfort level. |

| Asynchronous Online | Make instructions available through eConestoga. Leave the activity flexible enough so that learners can choose either a digital or analogue (paper and pen) option to match their skills and comfort level. Set up a discussion board for learners to show their work, and explain their thinking process. |

References

[1] Haugwitz, M., Nesbit, J. C., & Sandmann, A. (2010). Cognitive ability and the instructional efficacy of collaborative concept mapping. Learning and individual differences, 20(5), 536-543.

[2] Novak, J. D., & Cañas, A. J. (2006). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct them. Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition, 1(1), 1-31.

[3] O’donnell, A. M., Dansereau, D. F., & Hall, R. H. (2002). Knowledge maps as scaffolds for cognitive processing. Educational psychology review, 14(1), 71-86.

[4] Schroeder, N. L., Nesbit, J. C., Anguiano, C. J., & Adesope, O. O. (2018). Studying and Constructing Concept Maps: a Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 431–455.

4 Responses

-

Pingback: Breakout Rooms – Faculty Learning Hub

I have a question: mind maps (that focuse on one key topic per each) can be subsets of a given concept map (series of interconnected maps)?

Hi Antonio, great question! Yes, mind maps can derive from concept maps, and the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably.