Managing Zoom Fatigue

By Mike Wong, PhD

Many of us have resorted to online platforms such as Zoom, Teams, or Skype for our virtual meetings, classes, and social interactions. While these platforms offer an excellent means for staying connected, you may have noticed that virtual interactions quickly drain you of energy. This global phenomenon has been termed “Zoom fatigue.”

Although the reasons for Zoom fatigue are not entirely known, there are at least several hypotheses to explain this phenomenon. Keep reading for tips on how to avoid (or minimize) Zoom fatigue.

Change Camera Use

In everyday face-to-face conversations, we are privy to a wealth of information from non-verbal cues, such as body language and facial expressions. Unfortunately, in synchronous video conversations, non-verbal cues may be difficult to interpret, as videos of individuals are confined to small rectangles on a screen, whose clarity is further dependent on the quality of one’s internet connection and camera.

According to Dr. Gianpiero Petriglieri (Associate Professor, INSEAD) and Dr. Marissa Shuffler (Associate Professor, Clemson University), virtual calls force individuals to allocate much of their attentional resources to reading these non-verbal cues, which can be tiring. Petriglieri and Shuffler both recommend making cameras optional to reduce the fatigue from attempting to read the nonverbal cues of participants or moving videos to the side (or to a second monitor), so they are not in your immediate view.

Check-in with Participants

With online synchronous communication, there is often a delay between the speaker and receiver, which can be uncomfortable. Koudenburg, Postmes, and Gordijn (2011) found that a brief conversational silence, even one that was not noticed consciously, led participants to be more likely to report experiencing negative emotions, including rejection. Schoenenberg, Raake, and Koeppe (2014) reported additionally that speakers were judged more negatively if there was a delay of only 1.2 seconds! If videos are completely absent, these feelings may be exacerbated during response delays because there is the added stress of not knowing whether we (or the participants) have lost connectivity.

Regular check-ins with the participants using discussions, polls, or activities may reduce some of the stress associated with communication delays.

Reduce Eye Strain

As we spend an increased amount of time on our devices (e.g., mobile devices, computers, television), some of us may be experiencing “digital eye strain,” a term used to describe visual symptoms that are related to prolonged viewing of digital screens. One of the more common symptoms of digital eye strain is eye fatigue, which is thought to result from eye dryness due to a reduced blink rate and the angle at which one views their screens.

Making sure the font is easy to read may reduce some of this eye strain. Studies have reported that blink rate, and subsequently eye dryness, may be improved with adequate font size and contrast.

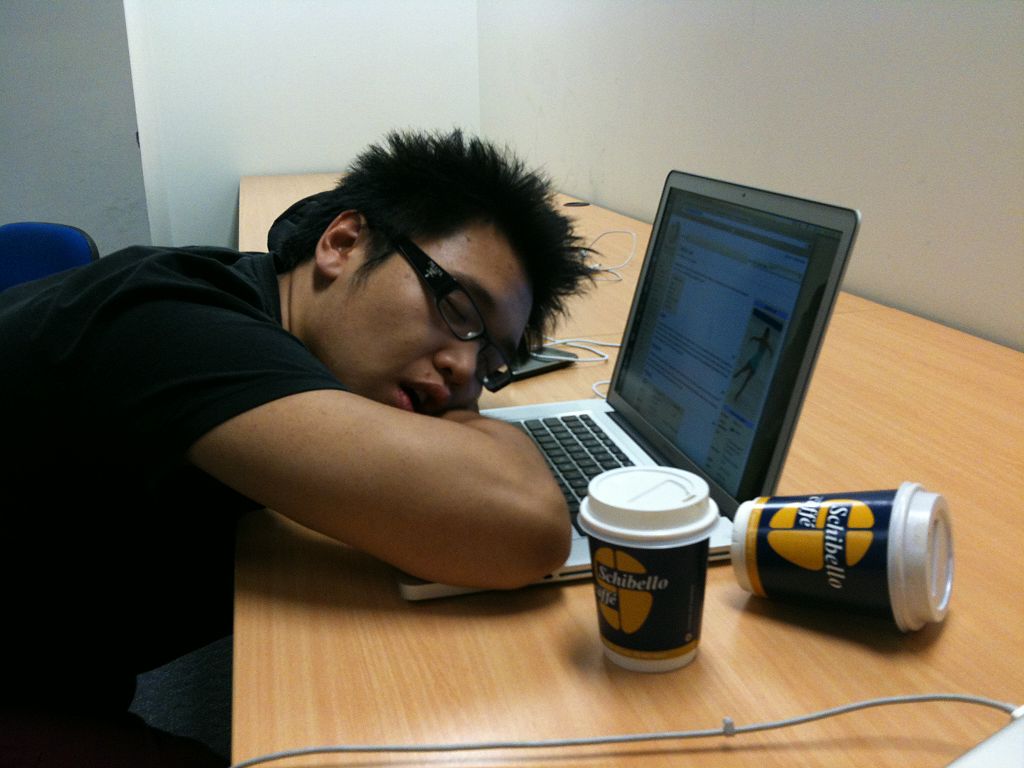

Take Breaks

Repeated and prolonged use of synchronous online tools for classes and online discussions can create signs of fatigue, including headaches, sleepiness, and irritability. Whatever the cause of Zoom fatigue may be for you, building in more breaks both during and between synchronous classes and meetings will likely help you feel less tired as you teach and work.

References

Jiang, M. (2020). The reason Zoom calls drain your energy. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200421-why-zoom-video-chats-are-so-exhausting

Koudenburg, N., Postmes, T., & Gordijn, E. H. (2011). Disrupting the flow: How brief silences in group conversations affect social needs. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(2), 512-515.

Rosenfield, M. (2016). Computer vision syndrome (aka digital eye strain). Optometry in Practice, 17(1), 1-10.

Schoenenberg, K., Raake, A., & Koeppe, J. (2014). Why are you so slow?–Misattribution of transmission delay to attributes of the conversation partner at the far-end. International journal of human-computer studies, 72(5), 477-487.

1 Response