Northern Lessons on Collaboration and Feedback

By Joel Beaupré, Teaching & Learning Consultant

With the expectation to spend so much time indoors lately, some have seized this opportunity to turn inward and find a more reflective, introspective approach to our work as educators.

Lately I’ve been pondering my earliest experiences as an educator and have questioned, “If I could go back and change anything about those first years of teaching – what would I do differently?” In this post, I’ll share one important lesson about that I admittedly learned the hard way during my experience as a novice teacher.

Where My Teaching Journey Began

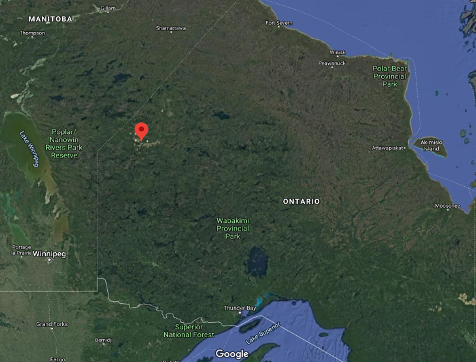

My introduction to teaching occurred in a unique setting – Sandy Lake First Nation, Ontario, a remote community about 600kms northwest of Thunder Bay.

My first assignment there was to teach Grade 8, which included a range of subjects for a group of about 20 students. At that time, I knew very little about Indigenous history and the realities of Canada’s residential schools: a deplorable system that was experienced first-hand by many of the parents and grandparents of the students I would work with. Even without this knowledge, I expected the cultural adjustment to a northern community to be challenging. Pedagogically, however, I trusted that I had all the tools and techniques needed to be immediately effective as an educator. Turns out I didn’t.

Self-Sufficiency: A Novice Mistake

Because I was a high academic achiever (especially while completing my Bachelor of Education), I started teaching with more confidence than many beginners (should) have. I had a strong grasp of theory, and one model I was especially familiar with was Differentiated Instruction (Tomlinson, 2000), which emphasizes the need to meet students where they’re at and take an individualized, responsive approach to facilitating learning. I knew that my students would have diverse needs, but I also believed that if I was willing to customize everyone’s learning experience on my own, I could exceed everyone’s expectations of what was achievable that year.

Part-way into the school year, it became apparent to me that my strategy to be fully responsible for providing customized care to each and every student wasn’t tenable. This became especially evident during math class, where I could see that a particular student wasn’t getting what he needed in spite of my best efforts to customize his resources and offer him more time and attention. The real mistake, as I came to realize, was that I could have referred him to external classroom supports (such as the resource teacher) much sooner than I did. Instead of taking a collaborative, consultative approach to my practice, I wanted to prove myself as a self-sufficient, autonomous educator. Instead of normalizing and advocating the use of school resources to support individual needs, I tried to be everything to everyone. I had perceived a referral to support as a deferral of responsibility, and that was just plain wrong.

If you’ve attended our “Teaching at Conestoga” workshop (one of six orientation sessions for new faculty at our college), you’ve been introduced to Lyon’s (2015) five stage model of teacher development (adapted from Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 1986), which outlines a teacher’s professional growth from the level of novice to the level of expert. Lyon claims that, at the novice stage, teachers abide by “rules for decision-making [that] are objectively defined [and] virtually context-free” (Lyon, 2015, p. 91).

In hindsight, it’s plain to see I wasn’t being mindful of the support my student could be given if I considered the broader school context; instead, I presumed a theoretical approach could be universally applied in my classroom alone. Thankfully, however, I was able to reconcile this mistake by making an important adjustment to my teaching practice.

Collaboration and Feedback as Turning Points

I connected with the resource teacher (who had far more teaching experience) to share my concerns about this student’s progress and to collaborate on a more appropriate learning plan. Through this dialogue, I received feedback (some positive, some not) on the attempts I made.

By collaborating with an expert, the student gained access to a more suitable learning environment that offered far more individualized learning than I possibly could provide.

Information and feedback were exchanged among the resource teacher, myself, and (most importantly) the student for the remainder of the school year. Reflections on mathematical concepts, exercises, and assessment results were shared and revised, and though this cycle of feedback and collaboration the student’s learning flourished. In fact, with this broader network of support in place he reached his goal of walking across the stage at the grade 8 graduation.

Thoughts and Takeaways

Benner (2014) suggests that teachers who wish to move beyond the novice level must become “keenly attuned to feedback and intently focused on the example of colleagues and mentors” (as cited in Lyon, 2015, p. 91). The resource teacher provided me with invaluable feedback on how to provide better differentiated instruction. My early teaching experience reinforced to me that feedback is important not only for student success but also for the educators who teach them.

As we prepare for the coming semester, let’s keep in mind that many students may be starting as ‘novices’ in their subject area, in their experience as remote learners, or in both. To facilitate their journey into becoming experts, it’s essential to provide individualized feedback at timely intervals and to take a collaborative approach to our practice so that all parties – teachers and learners – are adequately supported.

For more information on delivering assessment feedback remotely, check out this workshop that Laura Stoutenburg and I begin facilitating in May 2020. This session is part of the Alternative Assessment Practices series that explores tools, strategies, and principles to support student assessment in a remote context.

For more details on individualized supports and referrals for students, check out this post on Universal Design for Learning for Remote Teaching provided by Conestoga’s Accessible Learning team.

References:

Lyon, L. J. (2015). Development of Teaching Expertise Viewed through the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 15(1), 88–105.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2000). Differentiated Instruction: Can It Work? Education Digest, 65(5), 25.