Getting Students to Participate in Breakout Rooms

“[B]reakout rooms do not always magically create engagement and higher levels of learning.”

(Saltz & Heckman, 2020, para. 16)

Breakout groups are used as a discussion technique to increase participation and group-based learning. However, pair and group activities can be cumbersome in online synchronous meetings, especially when, as professor, you cannot see all groups and monitor student conversations at the same time (Reinholz et al., 2020).

If your students are not participating in online breakout rooms to your expectations, it may be worthwhile to reflect on how you might reflect on the meaning of the silence, provide more task clarity, and instil greater confidence in students for breakouts.

Note: if you are looking for more information on setting up and using breakout rooms, see this tech for teaching post, Breakout Rooms.

The Meaning of Silence

Faculty in the Western post-secondary classroom may perceive student silence as negative or disrespectful, or as a sign of disengagement (Jia et al., 2021). However, students from diverse national, ethnic, cultural, and religious backgrounds may have different and positive ideas about their silence in class. Students may view their silence as a form of respect (Yamada, 2015), connectedness (Covarrubias, 2007), concentration (Cronin, 2009), and reflective thought (Li, 2020). Students may have reasons for being silent that are unrelated to common assumptions about non-participating students.

Before calling classes or individual students for silence in breakouts, seek to understand what students think about silence and explain when silence and speech are important in the class for learning. Consider developing alternative activities for those who are unable to speak in breakouts.

Providing Clarity for Students

Here are some ideas on designing your breakout activities to clarify value, purpose, and steps.

Say why the breakout activity matters

Breakout assignments should connect directly to both the lesson’s learning outcomes and upcoming assignments. Even if your breakout activity is meant to be light-hearted and fun, students may not see value in participating if it does not appear to be assignment related. Describe the goal of the activity as it relates to the assignment.

- Reflective teaching questions: How closely related to the upcoming assignment is my breakout room activity? What can I say to connect participation with assignment preparation?

Be clear about the task

When students do not understand task instructions, they are more likely to disengage. Formulate clear, highly specific tasks; whenever possible, give activities that require no more than a few steps. Use meeting tools to share the prompt and steps so students may reference them while in breakout rooms.

Reflective teaching questions: How specific is the task or activity I am asking students to complete? How can I ensure that key instructions are still available to them while they are in the breakout room?

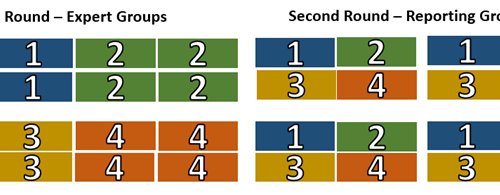

Set breakout group member roles

Group roles help collaborative learning activities to run smoothly; however, students may be shy or hesitant to arrange themselves in roles to complete group tasks. Saltz and Heckman (2021) note in their literature review that while providing too much structure for a role can negatively affect motivation, roles like the “summarizer” can improve learning process and outcomes.

- Reflective teaching questions: How much do my students know about the duties required for group work? What can I describe to about key roles of (facilitator, recorder, timekeeper, summarizer) to help group work run smoothly?

Give parameters and choices

Set parameters and limited options can help save a group time with decision-making. Open topics or too many choices can lead the groups to spending time trying to figure out how they will proceed.

- Reflective teaching questions: How can I provide students with limited but varied choices in their breakout groups?

Demo or provide an example

In their findings on a study on pair computer programming work in Zoom, Li (2021) advise: “In a virtual classroom, a clear tutorial at the beginning can help educators engage students in the task that they need to complete” (p.93). Demonstrate what you want students to do, then confirm understanding by ask students to repeat back or paraphrase key steps.

- Reflective teaching questions: What should I model or demonstrate before sending students to breakout rooms? How can the group affirm their understanding before being sent to breakouts?

Give groups a way to document their work

Documentation provides evidence of student learning. Used in a breakout room, collaborative documents, such as graphic organizers or supported drawings, help to guide groups to complete tasks or steps. Group work note-taking can also help shy or quiet students to contribute to group work.

- Reflective teaching questions: How do my students document their group work? What tools can I provide for them to help them keep track and share back what they completed as a group?

Monitor groups actively

Although breakout rooms give autonomy to students, it is a good idea monitor screen and mic activity from the main room (breakout window). You might also wish to visit groups to ensure they are on task and aren’t stuck (Reinholz et al., 2020). Participation checks also reinforce the expectations you set about active participation in group work by all (Li et al., 2021).

Reflective teaching questions: What instructions can I give for seeking support from me if students have a problem or need help? How can I circulate among breakout groups to help students stay on task?

In their research on online pair work, Saltz & Heckman (2020) found “that the practice of just sending students into a breakout room without much structure is not ideal” (para. 62). For breakouts to be successful, students must be clear about why the activity matters, what they are supposed to do, and how you are available to support them to achieve the task or goal.

Boosting Student Confidence

Here are some ideas to build student confidence as well as promote accountaiblity while working in breakout groups.

Make small breakout groups

Larger groups can lead to dominant voices “running” the group or to “group think,” in which everyone agrees out of a desire to belong or pressure to conform. Smaller groups–anywhere from 3 to 5–give students added accountability for participation as well as more room to participate. Li et al. (2021) suggest “different pairing methods to improve diversity and to increase creativity” (p. 94).

- Reflective teaching questions: What group size allows for diversity, but still allows everyone to participate in some way?

Show that you prioritize breakout room time

More time for breakout group activities, and a higher frequency of breakout groups within a lesson, both show that you prioritize group work and student particiption in breakout activities. At the same time, avoid leaving students on their own for too long by ensuring typical breakout group activities do not exceed 15 minutes.

- Reflective teaching questions: How can I make breakout groups a part of every class? How can I give students enough time in breakouts so that they are able to complete the task together?

Keep breakout room members the same

Rotating students in groups may appear to allow students to meet each other, but Reinholz et al. (2020) found that consistent student groupings helped to support students to maintain social bonds. At least for a period of time (such as one class), consider using the same breakout groups.

- Reflective teaching questions: How much more likely are students to get comfortable speaking with each other when they meet together repeatedly in breakout groups?

Make tasks relevant, meaningful, and interesting

Students are more likely to speak and participate on topics they have prior knowledge about and/or they care about. Involve students by asking them to complete tasks that allow them to share their knowledge. Or, have students to help to form breakout activities by asking them to supply topics.

- Reflective teaching questions: How can I utilize students’ prior cultural, professional, and personal knowledge in breakout group activities? What topics and skills will they be eager to share about?

Give students a chance to read or think before the breakout room

Some students may benefit from quiet time before group work to recall what they know and process what is being asked of them. Silent reflection and writing time for a few minutes before a breakout activity can help ready for active discussion time.

- Reflective practice questions: What reflection questions and quiet writing time might help students to formulate ideas and prepare for breakout groups?

Remind students about the importance of equitable participation

Students may not feel they can contribute to breakout tasks if they do not have the “right” answers. Remind students that behaviours like active listening to the unique perspectives that each student brings can help to solve challenging problems.

- Reflective teaching questions: How do I remind students that their unique perspectives are valuable? What emphasis can I place on active listening and turn-taking active listening so everyone has a chance to share?

Provide a healthy no-stakes competition between breakout groups

No-stakes or “friendly competition” between groups can promote task completion and group cohesion. However, students may be unfamiliar or uncomfortable competing in groups. “Losing” a competition may also be discouraging, even when there are no stakes. Competitions are likely to be more effective only after rapport exists among classmates.

It strongly recommended that you remind students the competition is not serious, and that the focus of the activity is learning, not who won. Perhaps the “winning” breakout group is the one that “best includes everyone’s voice or talents” in their collective response or solution.

- Reflective teaching questions: Is friendly, no-stakes competition a good way to motivate my students to participate? How can I provide success criteria, yet encourage learning for all?

Reinholz et al. (2020) found in their recent study on synchronous breakout groups that male often students spoke more than female students, but female students and students of colour were more likely to speak up in breakout groups than in whole-class time. Your diverse students may be more likely to participate actively and equitably if they feel confident and supported in completing the task together.

References

Covarrubias, P. (2007). (Un)Biased in western theory: Generative silence in American Indian communication. Communication Monographs, 74(2), 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750701393071

Cronin, J. G.R. (2009). Towards new understandings of silence. History of Art, University College Cork: Invited Seminars. https://cora.ucc.ie/handle/10468/206

Jia, Y., Yue, Y., Wang, X., Luo, Z., Li, Y. (2021). Negative silence in the classroom: A cross-sectional study of undergraduate nursing students, Nurse Education Today, 13 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105221.

Li, L., Xu, L., He, Y., He, W., Pribesh, S., Watson, S. M., & Major, D. A. (2021). Facilitating online learning via Zoom breakout room technology : A case of pair programming involving students with learning

disabilities. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 48, 87-100.

Li, L. (2020). Teaching beyond words: “silence” and its pedagogical implications discoursed in the early classical texts of Confucianism, Daoism and Zen Buddhism. Educational Philosophy & Theory, 52(7), 759–768. https://doi-org.conestoga.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1684896

Reinholz, D. L., Stone-Johnstone, A., White, I., Sianez, L. M., Jr, & Shah, N. (2020). A pandemic crash course: Learning to teach equitably in synchronous online classes. CBE Life Sciences Education, 19(4), 60-75.

Saltz, J., & Heckman, R. (2020). Using structured pair activities in a distributed online breakout room. Online Learning Journal, 24(1), 227+.

Yamada, H. (2015). Yappari, as I thought: Listener talk in Japanese communication. Global Advances in Business and Communications Conference & Journal, 4:(1), Article 3.