Imposter Phenomenon

Have you ever found yourself standing in front of a class, all eyes on you, as you click through your slides, or ask a provocative higher-order thinking question for students to reflect on, only to become suddenly, vividly, conscious of the fact that you’re teaching in a post-secondary institution? That these learners in front of you are looking to you as the expert in the room?! Your mind may start to race: am I really qualified to be here? Can the students somehow tell I was up until 2 a.m. re-teaching myself some of these key concepts and definitions before introducing them in class today? Might there be some sort of bouncer waiting at the door for me when class lets out, ready to question how I snuck in here in the first place, and announce to everyone that I’m a fraud!

If you’ve ever experienced any of these feelings of professional incompetence or intellectual self-doubt, you are not alone. And it’s likely helpful for you to know that these feelings are particularly common among post-secondary educators (Jöstl et al., 2012; Williams, 2021).

In this hub post, we’ll define and discuss the origins of the imposter phenomenon (and explain why we prefer this term over the commonly used “imposter syndrome”). We’ll share some research about the various “cycles” those familiar with the imposter phenomenon might get caught up in, and discuss why post-secondary educators are particularly prone to these feelings of fraudulence. And finally, we’ll zoom out to look at structural (as opposed to individual) forces at play that impact the imposter phenomenon “cycles”, and provide some tips to help alleviate these feelings.

Imposter “phenomenon” or “syndrome”?

You’ve likely heard the term “imposter syndrome” in popular culture in recent years. Countless political pundits, celebrities, and others in the spotlight have been going public and sharing their own experiences of overcoming professional self-doubt. However, the researchers (Clance & Imes) who initially uncovered this trend in 1978 when looking at experiences of high-achieving women in academic settings, preferred (and still prefer) the term “imposter phenomenon” for important reasons. Namely, a “syndrome” seems chronic, individual, and pathological–something one might be diagnosed with that they’ll have to spend the rest of their life working through. Alternately, a “phenomenon” assumes that this is a curious trend, and suggests that some level of social exploration about why particular groups of people, in particular settings, might all be feeling this way should be undertaken. Clance and Imes (1978) who coined the term “imposter phenomenon”, also remind us that most people who experience it don’t feel this way about everything in their lives. I.e. it’s not a general lack of “self-confidence” as one may feel completely competent working in a certain professional setting, in their personal life etc. but then suddenly feel like a fraud if asked to teach a college course or give a keynote address at an academic conference even if they are clearly qualified.

Many researchers have expanded on Clance and Imes’ work over the past few decades, and the definition of “imposter phenomenon” has evolved. Rudenga & Gravett (2019) describe it as:

“The belief, despite evidence to the contrary, that one has fooled others into overestimating one’s abilities and will eventually be exposed as a fraud” (p. 1).

Additionally, framing this experience as a phenomenon also suggests that it is not entirely negative. In fact, there are many positive reasons why someone might experience these feelings. For example, it can be an indication that you care a great deal about the work you do and how it comes across to others. It can be a sign that you set the bar high for yourself; are reflective; have a “growth mindset” and aspire to continued improvement. It can also lead to deeper connections with colleagues brought about by discussing feelings related to impostor phenomenon cycles (Rudenga & Gravett, 2019).

The Imposter Phenomenon Cycle

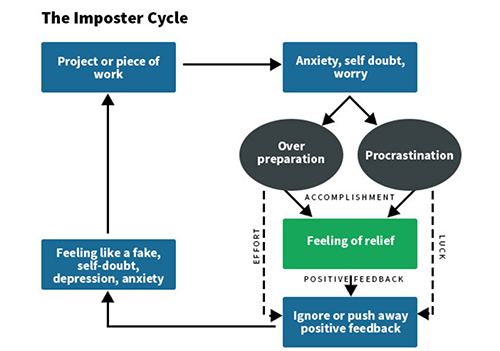

The imposter phenomenon cycle that Clance et al. (1985) developed outlines two different paths one might take when a new project or piece of work comes their way (in the case of teaching, we can imagine we’re assigned a new course we’ve not taught before). In some cases, those experiencing the imposter phenomenon will feel anxious and worried that they aren’t up to the task and will over-prepare as a result–pouring much more time and energy than necessary into planning each lesson. Others may have difficulty “diving in” and getting started in the first place, and so will procrastinate instead as their fear of failing at the task may feel overwhelming. In both cases, when the project ends up going well (as it usually does because those experiencing the imposter phenomenon are typically highly competent and well-equipped to handle the task they’ve been given), it can be hard for them to accept that their success was a result of their abilities. Instead, they may attribute their success to either hard work (in the case of over-preparation), or luck (for those who procrastinated). The internal dialogue persists (“That only went well because I worked twice as hard as my more capable colleagues” or “I just got lucky–the group of students was particularly engaged today and made it easy on me”) and feelings of self-doubt are re-affirmed.

Why are those working in academia particularly prone to these feelings?

While the literature shows that many professionals in various fields suffer from feelings of intellectual self-doubt, Williams (2021) draws on research that reveals that those working in academia (graduate students or full or part-time faculty) are especially prone to experiencing the imposter phenomenon cycle. Some reasons for this are:

- Academic environments are particularly competitive (and one often finds themselves amongst high-achieving others).

- The “publish or perish” culture in many post-secondary settings adds additional pressure.

- The stakes are high when you teach. Faculty are expected to be “present” in front of the classroom in ways that other professions don’t require. Additionally, faculty are expected to be subject area experts and also to possess pedagogical expertise and strong interpersonal skills to understand and respond to diverse student needs in the moment.

- Unlike many other professions (like doctors, nurses, or elementary or high school teachers), faculty members rarely have the occasion to apprentice or watch expert professors in their fields in action. So it can be hard to envision or set a standard for one’s self about what “successful” teaching looks like.

- Performance goals tend to be more vague than other professions.

- Feedback is often delayed (SATs typically only come at the end of term, and faculty members may not be observed by chairs/ colleagues at all during their first semesters/ years of teaching).

Potential consequences of getting stuck in the imposter phenomenon cycle

Even though the imposter phenomenon is not a pathological condition, according to Sakulku & Alexander (2011) there are some potential consequences for professionals who get “stuck” in this cycle for a period of time.

For example, over-working/ over-preparation (feeling that one needs to do more than others to achieve the same results) often means that the time, energy, and effort invested for these folks far exceeds what is reasonable for the task at hand. This additional time and energy devoted to over-preparation can interfere with other personal and professional tasks (the individual may recognize this fact but fear that a change of pattern/ breaking of the cycle will result in failure). Those who get stuck in the imposter phenomenon cycle also have a tendency to disregard their success; they often have very high expectations for themselves which are near-impossible to achieve. (I.e. there will always be a gap between their performance and their “ideal standard”) p. 76.

How can you alleviate some of these feelings/ break free from the imposter phenomenon cycle?

If you feel yourself “stuck” in the imposter phenomenon cycle and want to make a change, there are a number of different things you can try. According to Rudenga & Gravett (2019) many folks find it helpful to:

- Talk with others from outside your workplace who also have been stuck in the IP cycle.

- Share experiences/ anxieties with mentors within your profession who can help you assess your work/ level of preparation more objectively.

- Take stock of your accomplishments. Spend some time looking over your CV to remind yourself of the extensive experience that led you to teaching and the unique qualifications you bring to the classroom.

- Set reasonable goals for yourself. Ask yourself “what would make you a ‘good’ teacher?” and then consider how you might measure whether you’re meeting these expectations week-to-week (i.e. don’t wait until the SAT at the end of the semester as the sole evaluation of your performance).

- Allot yourself ‘panic breaks” that entail setting limits for how long you’ll allow yourself to worry about something. (I.e. “I’ll only let myself worry for the full length of this song as I drive to campus, and then I’ll have worried enough” or “I can do a good enough job teaching if I put in 2 hours a week lesson planning. Hence, after 7 p.m. on Monday, I will be done worrying about this, and will trust that I have prepared enough to teach on Tuesday”).

- You can request that Teaching and Learning come into your classroom and conduct a Developmental Observation of Teaching to offer an “outside” perspective if you have difficulty judging whether your teaching strategies are effective and to help assess whether you’re meeting the goals you’ve set for yourself.

- Gather a group of colleagues together to write up and share “failure CVs” (We so often only hear about one another’s successes and forget that we all encounter “failures” on a regular basis too).

- You can shift self-talk language to focus on achievements instead of “luck”.

- You can practice self-compassion and acknowledge the broader context (remember that there are inequalities and structural barriers in academia). Situational and environmental factors (completely outside of your control) may have a negative impact on your well-being and self-confidence.

The bigger picture (it’s not just you!)

As noted above, even though these feelings of “imposterism” might feel like a personal/ individual problem, it’s important to keep the broader context in mind. In a recent Harvard Business Review article titled “Stop telling women they have impostor syndrome,” Tulshyan & Burey (2021) critiqued Clance & Imes (1978) findings and methodology, arguing that in many cases, especially for women of colour, imposter phenomenon is “not an illusion but the result of systemic bias and exclusion”. They noted that Initial research on the Imposer Phenomenon, did not take into account “the effects of systemic racism, classism, xenophobia, and other biases… The answer to overcoming imposter syndrome is not to fix individuals but to create an environment that fosters a number of different leadership styles and where diversity of racial, ethnic, and gender identities is viewed as just as professional as the current model” (para. 8).

That is to say, sometimes you might feel like an imposter due to historic inequalities or systemic barriers. In higher education in Canada, many of us grew up with a particular idea in mind of what a post-secondary professor looked and sounded like (typically male, white, able-bodied, English-speaking, and heterosexual). These images have been re-enforced by popular culture representations and are ingrained in the public imagination to some extent. If you yourself are not male, white, able-bodied and hetero-sexual, then part of the reason you may question your competence or wonder if you really belong at the front of the classroom is because you haven’t had as many models who are like you to look up to. In these cases, it is important to remind yourself that it is not only okay to do things differently and embrace who you are, but vital that we have faculty at the front of the classroom who bring with them diverse life experiences and perspectives on the world.

References

Abrams, (2018). June 20. Yes, Impostor Syndrome Is Real. Here’s How to Deal With It. Time Magazine. https://time.com/5312483/how-to-deal-with-impostor-syndrome/

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 15(3), 241–247.

Clance, P.R. (1985). The impostor phenomenon: When success makes you feel like a fake. New York: Bantam Books (softback).

Clance, P. R., Dingman, D., Reviere, S.L., & Stober, D. R. (1995). Impostor Phenomenon in an interpersonal/social context: Origins and treatment. Women and Therapy, 16, 79-96.

Jöstl, G., Bergsmann, E., Lüftenegger, M., Schober, Spiel, B. (2012). When will they blow my cover? The Impostor Phenomenon among Austrian doctoral students. Journal of Psychology, 220(2), 109-120.

Rudenga, K.J. and Gravett, E.O. (2019), Impostor Phenomenon in Educational Developers. To Improve the Academy, 38: 1-17.

Sakulku, J & Alexander, J. (2011) The Imposter Phenomenon. International Journal of Behavioural Science, 6(1). 73-92.

Tulshyan, & Burey, J. (2021a) Feb 11. Stop Telling Women They have Imposter Syndrome. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2021/02/stop-telling-women-they-have-imposter-syndrome

Tulshyan, R & Burey, J., (2021b). July 14. How to End Imposter Syndrome in your Workplace. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2021/07/end-imposter-syndrome-in-your-workplace

Willimas, A.T. (2021) Imposter Phenomenon in the Classroom. Brown University Centre for Teaching and Learning. Retrieved from: https://www.brown.edu/sheridan/impostor-phenomenon-classroom