Pacing

Have you ever struggled to fit all of the weekly content you need to cover into your one or two-hour class meeting and noticed yourself rushing through the material? Or facilitated an in-class activity you thought would last 15 minutes but saw that students seemed to lose focus or get distracted after only 5? Perhaps you yourself have sat through workshops, classes, or meetings that seemed to drag on for much longer than necessary, and so have experienced firsthand the feelings of frustration that arise when content-sharing is not paced properly. This hub post will explain what pacing is and how it can help enhance student engagement and knowledge retention when incorporated into lesson planning and delivery.

What is pacing in teaching and why is it important?

Whether or not you’ve ever stopped to reflect on it, your course overall; each of your lessons; and all components and activities within these lessons move along at a particular pace. Goldsmith (2009), describes pacing as “the rhythm and timing of classroom activities or units, which includes the way time is allocated to each classroom component and the process of how one decides that it is the right moment to change to another activity…” (p. 33). The teacher-development group Impact Teachers (2016) describes effective pacing even more simply as “the skill of creating a perception that a class is moving at just the right speed for the students” (para. 4).

Finding the right pace for your course, weekly lessons, and components and activities within each lesson is key. When you pace effectively, students will remain engaged and trusting. If you move too slowly, you risk “losing” students as they become bored or distracted; and if you move too fast learners won’t be able to keep up and may feel discouraged.

What can impact pacing?

Timing

Simmons (2020) suggests that faculty think of “timing” in 3 different ways: Allocated time; Instructional time, and Engaged time.

Allocated time is “the amount of time teachers plan to devote to instructional activities in a lesson.” (e.g. If you teach a section of a course once weekly from 2-4 p.m. on Thursday, you know that class will need to end by 3:50 and students will also need a 10-minute break in the middle, so your actual allocated time for the full lesson is only 1 hour and 40 mins.)

Instructional time is “the amount of allocated time dedicated to a specific instructional activity that a teacher (or students) actually spend on that activity.” (e.g. the pre-assessment component of this week’s lesson will last for 8 mins; the summary for 2 mins.)

Engaged time is defined as the amount of time during the lesson when students are authentically engaged in specific activities. Learning is most effective when “engaged time” is maximized; where “…students aren’t just attending to direct instruction or doing the activities planned, but are substantively engaged as they do so. In other words, students put forth cognitive effort, actively participate, and commit to the task” (p. 2).

Some aspects of timing are out of your control as a faculty member (i.e. you can’t decide that class will be 3 hours instead of 2 one week if there’s extra content to cover). But you can control aspects of instructional and engaged time when lesson planning in advance and facilitating class discussions and activities in the moment.

Transitions

Any well-planned and effectively paced lesson will have multiple components and part of the faculty member’s job is to seamlessly transition between them (Alber, 2016). Goldsmith (2009) reminds us that “transitions are not the framing of the next activity, but rather the time in between activities… transitions end the moment the instructor begins to present the next activity” (p. 34). For example, a transition might entail a faculty member saying “Okay everyone, It’s time to stop your small group discussion now.” Or “Alright, it’s been 7 minutes of quiet reflection and writing. Please bring your papers to the front and then we’re going to come back together as a large group now.” Transitions can be challenging for some students and so the clearer your instructions are, the more obvious your sequencing is (i.e. why and how one activity connects and leads into the next), the more willing students will be to trust the process. In many cases, being clear and upfront with students about how you are “chunking” weekly content, allows them to see the bigger picture, and better understand when and why transitions are necessary.

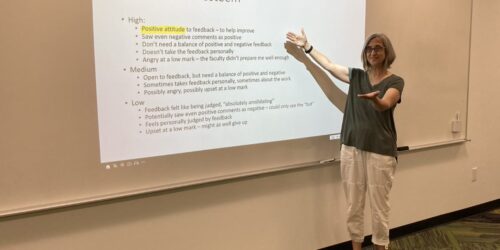

Weak or strong differentiating

Of course, you may plan your lessons down to the minute, carefully allocating adequate “engaged” time each week, only to note during delivery that the predetermined timing doesn’t feel “right”. Hoadley (2003) speaks about teachers having “strong” or “weak” differentiating pacing. “Strong differentiating pacing occurs where there is variation in pace according to the teacher’s assessment of the demands of the pedagogical situation—the content of the lesson and the individual rate of learning of learners in the class. With strong differentiating pacing individual learner needs and specific contents are identified and the pace is varied accordingly” (p.268). Weak differentiating pacing occurs when the teacher does not adapt their lesson plan or pacing according to specific learner needs or levels of comprehension in the moment.

At Conestoga, we believe that faculty’s congruence with students is vital and we therefore encourage strong differentiating pacing. That is to say, if you teach multiple sections of the same course in the same semester, it’s possible you’ll pace and plan your lessons slightly differently as different groups of students have different strengths and needs (e.g. perhaps one section is always eager to respond to higher order large group discussion questions, whereas students in another section appear resistant to doing so. When planning and delivering your lesson, you might use the same question prompt as part of a large group discussion activity for section one but a think-pair-share activity for section two—leaving students enough time to reflect individually, share ideas with a partner, and then invite those who are willing to share their thoughts with the wider class).

Key tips to pace more effectively

- Share the agenda and clearly state the key course or unit learning outcome(s) at the start of class, assuring that each component of the lesson clearly aligns with this/ these objective(s).

- Stay on topic, but change instructional strategies, types of activities, or methods of presentation regularly to ensure students are refreshed.

- Curate your content! Just because you have been given a PowerPoint slide deck with 45 slides for a single 2-hour class, doesn’t mean you need to spend the same amount of time on each slide. In fact, you may even opt not to show each and every slide in class each week. As the faculty member teaching this course, you can use your discretion as to which parts of the lesson are most vital and aligned with the specific course or unit outcome being addressed—and spend the majority of time sharing this content in engaging ways that highlight for students why the material is relevant to their lives and careers today. (Students can always access the full slide deck in econestoga if they’d like to seek out additional information).

- Scaffold and sequence your lessons so that each new component naturally builds on the ones that came before. (For example, if you’re teaching a lesson where you want students to 1) identify types and forms of autobiography and memoir and 2) discuss ideas of history, truth, and realism as they relate to life writing, you might want to open the lesson by sharing certain definitions of autobiography and memoir; then put students into small groups where they are each given an excerpt from a different type of autobiography/ memoir to read through as part of a jigsaw activity—where each group will be asked to share findings with the wider class. After these mini-presentations, you might close class by sharing an example that complicates definitions provided at the start to expand students’ thinking—perhaps a piece of autobiographic visual art or film, or a written text where the narrator’s perspective or memory is untrustworthy/ contested. This could lead to a large group discussion where students are prompted by a higher-order thinking question such as: “Would ____ example be considered an autobiography/ memoir? Why/ why not?”

- Incorporate transitions (your cue to students that one component of the lesson is wrapping up and another is about to begin).

- Assure that materials are set up and available for all lesson components (Alber, 2016). (i.e. if you’re going to share a MentiMeter poll as a bridge-in at the start of class, make sure the link is already open on your computer before students arrive. If you’re going to ask students to write ideas onto sticky notes and post them on the whiteboard in the middle of class, make sure that each table has these papers and markers ready and waiting for them before the activity is introduced. A lot of teaching time is wasted, and pacing is thrown off when lessons are interrupted by faculty searching for website links or walking around the room distributing materials mid-lesson.

- Plan key active learning components ahead of time. If students will be engaging in a large group discussion or think-pair-share activity in response to a particular higher-order thinking prompt, for example, be sure to script this question and activity instructions in advance and include them on a PowerPoint slide. This will show students that you’ve deliberately thought through this part of the lesson in advance, and will also ensure that the wording is clear so no time is wasted re-phrasing what is being asked or what the expectations and parameters are.

- Note the timing for different components when lesson planning. (e.g. this “gallery walk” will likely take 10 mins). Of course, timing might change slightly in the moment depending on student needs and reactions, but laying out a timeline on your BOPPPS lesson plan will help clarify for you which aspects of the lesson are intended to be shorter or longer and you can use this as a “map” when unanticipated learner needs or reactions come up in the moment.

- Effectively paced lessons have a sense of “urgency” to them… some faculty find it helpful to keep a timer on their desk (Alber, 2016). This can both help keep them on track and also communicate to students that there is a lot of important content to cover in class so it’s vital they arrive on time, and return promptly after breaks. This sense of urgency can heighten the learning experience and help students feel that it’s worth showing up to class and being on task because faculty are also upholding their end of the teacher-student “contract.”

- You, the teacher. Of course, even with the best-laid plans, much of “pacing” comes down to you. Your mood, comfort level, breathing patterns, and general energy level on any given day also have a big impact on how the class is paced. Delivery skills can be practiced and improved upon, but it is generally always a good idea to ensure you take big, deep breaths before class begins, or if things start to feel challenging mid-way through the lesson. Do try as well to ensure you’re leaving adequate time for students to respond to questions you pose.

References

Alber, R. (2012). Instructional pacing: how do your lessons flow? Edutopia. Retrieved from: https://www.edutopia.org/blog/instructional-pacing-tips-rebecca-alber

Goldsmith, J. (2009). Pacing and time allocation at the micro- and meso-level within the class hour: Why pacing is important, how to study it, and what it implies for individual lesson planning. Journal of Teaching & Learning Language and Literature, 1(1), p. 30-48.

Hoadley, U. (2003). Time to learn: pacing and the external framing of teachers’ work. Journal of Education for Teaching, 29(3), p. 265-274.

Impact Teachers. (2016) Teacher tips: Pace. Retrieved from: https://impactteachers.com/blog/pace-2/

Simmons, C. (2020). Pacing lessons for optimal learning. Association for Learning and Curriculum Development, 77 (9). Retrieved from: https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/pacing-lessons-for-optimal-learning

Great suggestions @laurenspring, I find effective lesson plans coupled with scaffolding throughout the lesson to be a powerful combination. Of course, all within the context of your final point about how to be an effective teacher-leader.