Creating a Rubric

Creating or refreshing a course? Looking for the best way to assess learning outcomes? Or are you trying to cut down on your grading time? Rubrics may be just the solution for your marking dilemmas.

Why do we need rubrics?

Not all assignments have straight-forward, yes or no answers. A rubric provides both the instructor and the students with a framework to understand the expectations of a task-based assignment in alignment with the course learning outcomes as well as the essential employability skills for the course. Furthermore, evidence is growing that rubrics can be effective in improving student performance in a wide variety of subject areas (see for example Auxtero and Callaman’s 2021 study of the use of rubrics to improve student performance in a calculus course).

When can a rubric be used?

Rubrics can be an appropriate choice for providing feedback for performance-based tasks such as reports, presentations, portfolios, projects, reflective assignments, and other multi-layered assessments. A rubric provides both the instructor and the students with a framework to align an assignment with the course learning outcomes as well as the essential employability skills for the course.

What does a rubric include?

According to Chowdhury (2018), a good rubric helps ensure both validity and reliability of the assessment tool, both of which are requirements stated in Conestoga’s Evaluation of Student Learning Policy (2021). Establishing criteria (the rows of the rubric) ensures that the assessment is fair and valid, measuring appropriate learning outcomes. Creating achievement level descriptors (the columns of the rubric) ensures reliability; faculty across sections of the course will be following the same indicators of what is expected for a particular grade. A good rubric also provides more structured feedback to students about their performance (Stanley, 2021).

The Format of an Analytic Rubric

| Elements | Level 1 (Lowest) | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 (Highest) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion 1 | |||||

| Criterion 2 | |||||

| Criterion 3 (and on…) |

Setting Criteria

In the cells of the left column of the rubric, you will find a series of criteria by which the assignment will be assessed. The following is a suggested process for adding criteria to your rubric.

- Identify the course learning outcomes and the essential employability skills relevant to the assessment.

- Identify your own expectations for the assessment. What are you looking for in a student’s submission? Criteria may be content related, process related, skill related, or language and format related. For example:

| Type of criterion | Example Criteria |

|---|---|

| Content | Explanation of research findings is accurate and thorough. OR Accuracy and thoroughness |

| Process | The necessary steps were included in solving the problem. OR Inclusion of necessary steps. |

| Skill | Critical reflection is evident. OR Evidence of critical reflection |

| Language / formatting | This is limited to less than 20% of the criteria and mark. Grammar, spelling, punctuation, and vocabulary choice are appropriate. OR Grammar, spelling, punctuation, and vocabulary choice |

- An assignment worth 20% or more of a course grade should have at least 5 criteria. A rubric for an assignment worth 25% or more should probably be reviewed by at least two people.

- Each criterion should align with the instructions for the assignment. For example, if you are marking for critical reflection, the assignment instructions should ask for critical reflection.

- Anything for which students can gain or lose marks should appear in one of the criteria of the rubric. It is not permissible to deduct marks for an expectation which has not been captured somewhere in the rubric.

- Anything that you are expecting students to achieve which is not supported by the course learning outcomes or the essential employability skills should be reconsidered.

- Subtractive marking is not permitted. You can’t add up the total and start subtracting for additional items such as typos.

Language criteria

If you include a criterion for language, ensure that it counts for less than 20% of the total mark. On one hand, language difficulties which affect your ability to understand the content of the assignment will adversely affect the criteria for content so will affect the overall mark already. If comprehensibility is not affected, on the other hand, a student should not have to fail an assignment because of a heavily weighted language mark.

Establishing Achievement Levels

The achievement levels for each criterion tie achievement descriptors to the number of marks earned. It is crucial that each descriptor be achievable and measurable without being too specific. For example, it is measurable to state that the language of the assignment contains some grammatical errors that do not impede clarity. It is too specific to state that the assignment contains fewer than 5 grammatical errors.

The achievement level or standard must be at the level expected in the credential you are teaching into. See The Ontario Qualifications Framework.

Reference the Grading Procedure

The achievement levels that you establish should coincide with the grading standards for your area as captured in the Conestoga College Grading Procedure. All descriptors in the rubric should conform to the description and guidelines contained in the Grading Procedure. Within those parameters you do have some options with respect to how detailed to make your rubric.

You’ve decided to create a rubric for your assignment, and you have identified assessment criteria which align to your course learning outcomes and essential employability skills. The next step is to create the achievement levels.

Identify Number of Levels

How many achievement levels should be included in a rubric? There are a number of options; following are some considerations.

| Levels | Description |

|---|---|

| 5 Levels | A five-level scheme has much to recommend it, especially for courses with passing grades of between 55 and 65. Decide which level constitutes a pass. You have a few options: A passing level centred as the third column allows for guidance to be provided on both sides of the passing grade. Two columns to the left of the passing level can distinguish between work which is within 10% of a pass and work which is well below passing. Two columns to the right of the passing level can distinguish between above average and outstanding work but won’t cover each alpha level above a pass individually. Making the passing level the second column provides you with more opportunity to describe the differences between upper levels of achievement. However, it gives less room for guidance for faculty in how to fairly mark and provide basic feedback for the range of marks below passing. |

| 4 Levels | Rubrics for courses with a higher passing grade (for example, 60% and higher) may benefit from 4 levels rather than 5 for the following reasons. The passing grade in these cases is already indicative of above average work. If you teach in a program with a high pass rate, you can always stay with a 5-level rubric, and the highest two levels can distinguish more specifically between an A and an A+ grade. |

| 3 levels (for evaluations under 5%) | A 3-level rubric will be far less common because it will not be detailed enough for an assignment which is worth more than a few percent of the overall course grade – anything worth enough points to sway an alpha grade should be more robust than 3 levels. However, you might consider this abbreviated rubric style in the following circumstances. A discussion post worth a very small amount of the course grade can be graded according to whether it is not present, present, or present and very well done. Similarly, a short reflection worth a very small amount of the course grade can be graded according to whether there is no real reflection included, some reflection included, or a thoughtful reflection is included. |

Write Achievement Level Descriptors

The key to an effective level descriptor is to be specific enough for clarity for both the faculty marking the assignment and the student reading the feedback but not so detailed as to make the rubric difficult for everyone to use. Consider the following:

- Write the pass level descriptors first. Describe what an acceptable level of achievement looks like for each criterion (Stanley et al. (2021) suggest that the “pass” descriptor should be identical to the criterion description in the far-left column).

- Write the pass level descriptors as positively as possible. The pass level descriptors are not meant to point out what the student cannot do. They are meant to point out what is a basic acceptable level of achievement.

- Next, add descriptors in relationship between acceptable (or simply “pass”) and outstanding on one side and “does not meet expectations” on the other.

- The descriptors can be in point form or complete sentences. Choose a style and be consistent.

- Choose the level of detail to include just enough detail to give guidance to both faculty and students. Save more specific critique for the comments section.

Assign Point Values to Criteria and Across Achievement Levels

The simplest method for assigning marks to levels is a 5-point or a 10-point system. This way the number of marks easily relates to percentages. However, there is room for variation as long as the numbers add up to the appropriate percentages based on the passing mark for your course / program and the equivalent percentages for an A, a B, etc.

If using a standard 5 or 10-point system, you can weight each criterion differently to ensure that content-based criteria receive more marks than criteria which are less central to the course learning outcomes.

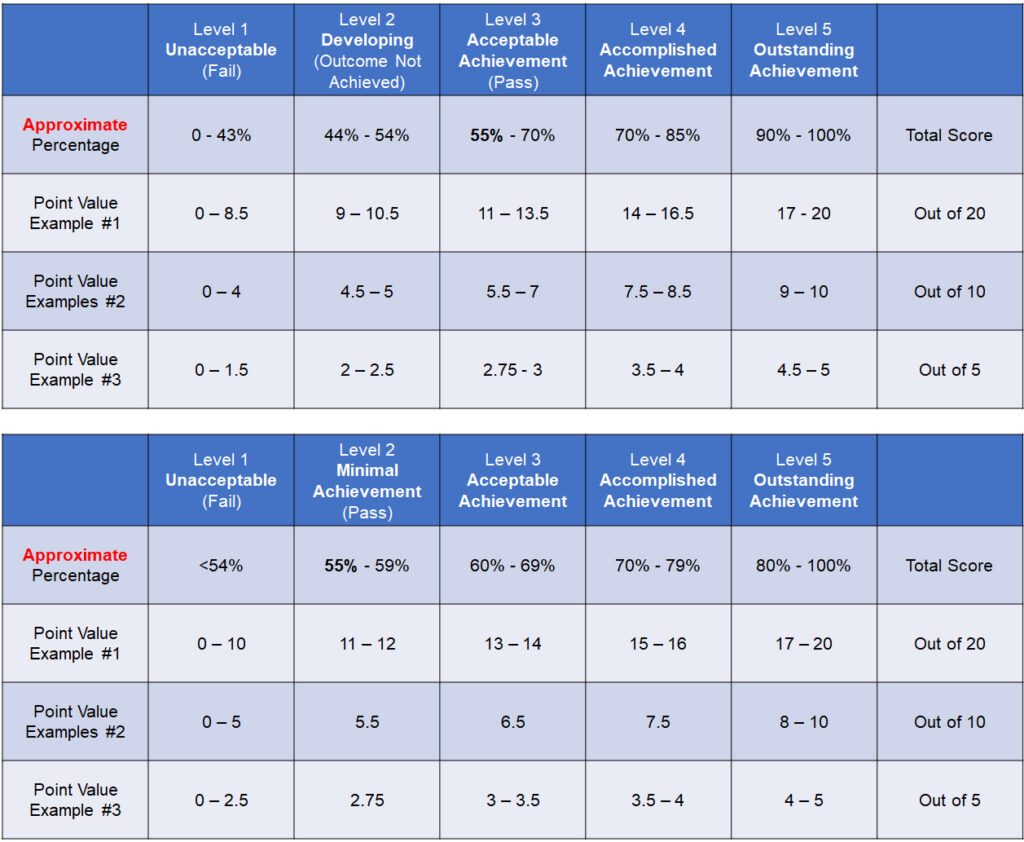

The figure below illustrates two example rubrics, with options for point value assignment across a criteria. The top chart demonstrates setting the “pass” criteria in the middle (Level 3), while the lower chart demonstrates seeing the “pass” criteria at Level 2. Important to note that both charts reference a course with passing grade of 55%. A recommendation is that you would remove the “Approximate Percentage” row from your student-facing rubric.

Step 4: Creating Space to Provide Specific Feedback

Do include a comment section for each criterion. In light of the achievement level descriptors, lengthy feedback comments are not required. However, students will benefit from specific comments regarding their work with respect to each criterion, especially if there is a range of point values within an achievement level. Remember, students who do well on their assignments appreciate comments as well.

Learn More

Learn more about rubrics and assessment practices in the Teaching and Learning Microcredential Evolving Assessment Practices

References

Auxtero, L. C., & Callaman, R. A. (2021). Rubric as a Learning Tool in Teaching Application of Derivatives in Basic Calculus. Journal of Research and Advances in Mathematics Education, 6(1), 46–58.

Conestoga College. (2020). Grading Procedure.

https://cms.conestogac.on.ca/sites/www/Shared%20Documents/Policies%20and%20Procedures/Academic%20Admin/Grading%20Procedure.pdf.

Conestoga College. (2021). Evaluation of Student Learning Policy.

https://cms.conestogac.on.ca/sites/www/Shared%20Documents/Policies%20and%20Procedures/Academic%20Admin/evaluation-of-student-learning-policy.pdf .

Chowdhury, F. (2018). Application of Rubrics in the Classroom: A Vital Tool for Improvement in Assessment, Feedback and Learning. International Education Studies; 12(1), 2019.

Stanley, D., Coman, S., Murdoch, D., & Stanley, K. (2020) Writing Exceptional (Specific, Student and Criterion-Focused) Rubrics for Nursing Studies. Nurse Education in Practice, 49, 102851. https://doi-org.eztest.ocls.ca/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102851

Further Reading (available in the Conestoga Library)

Quinlan, A. M. (2012). A complete guide to rubrics. [electronic resource] : assessment made easy for teachers of K-college (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Stevens, D. D., & Levi, A. (2005). Introduction to rubrics : An assessment tool to save Grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning: Vol. 1st ed. Stylus Publishing.

1 Response