Mental Health: The Bigger Picture

The United Nations has declared Oct 10th World Mental Health Day. Throughout the month of October each year, the UN encourages industries and organizations across the globe to: “spotlight mental health around the world, raise awareness of mental health issues and encourage efforts to support those experiencing mental health issues” (“World, N.D.)

Mental Health has become somewhat of a buzz-term lately. We tend to hear about mental health and mental wellness in popular culture and the workplace on a regular basis. Even major corporations have launched campaigns to help destigmatize mental health struggles and to encourage people to share their stories with one another. It would be surprising, in fact, if you weren’t already regularly taking stock of your own mental health, and astutely aware of the mental health of those (family members, colleagues, students) around you. Despite these trends towards destigmatization and open conversation, it’s important to remember that mental health is a continuum and struggles rarely represent a tidy trajectory from “ill” to “well”. This hub post seeks to offer a broader perspective about what we’re really talking about when we discuss mental health. It also explores the need to move away from a solely “medical model” understanding of mental health, and towards a “biopsychosocial model”–especially when considering the post-secondary student experience. It offers practical tools you can use if you find yourself supporting a student who is struggling, while also outlining critical and legitimate reasons certain individuals may be hesitant to seek formal help and/or diagnoses.

What is Mental Health Anyways?

Experiencing suffering and distress is a part of being human. It’s impossible not to have emotionally and psychologically challenging chapters of one’s life. Sometimes it can feel like these dark moments will never end even though we humans are, in fact, built to get through hard things. Along the way, we may try out different (both healthy and unhealthy) ways of coping in these hard times. Sometimes we’ll need to rely on others (professionals, peers, family members) to help us get through. We may also notice worrisome changes in the way we think, feel, and behave during these times and wonder how, and struggle to break free from these unhelpful thoughts, emotions, and behaviours.

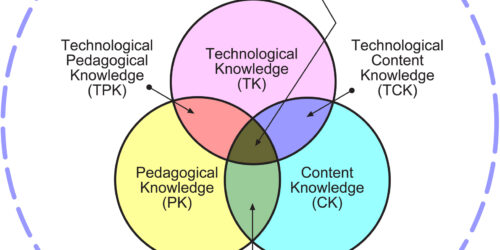

Even though the words “mental health” may in our imaginations be associated with brain chemistry, we know that there’s much more to the story than that. The things we’re going through in life, the support systems we do or don’t have in place, the way our bodies feel… all of these things can impact our “mental” health. Additionally, what we consider “normal” or healthy is also historically and culturally contingent. As Kingma (2013) reminds us: “the concept of mental illness relies on norms or values which define disorders as bad or undesirable and which are sometimes even understood as socially or historically constructed” (p. 365, as cited in Jelscha, 2017, p. 486).

Conceptualizing Mental Health Struggles Today

Psychiatry’s problematic history

Psychiatry has a long and problematic history. Though things have improved somewhat over the centuries, it’s important to acknowledge psychiatry’s origins, questionable historic “treatment” approaches, and discriminatory diagnoses. Some of these include: “hysteria” which unnecessarily landed many women in asylums during the 19th and 20th centuries (Tasca et al., 2012); “homosexuality”–which was only removed from the diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders (DSM) in the year 1973; and “pibloktoq” or “arctic hysteria” a label applied to Inuit women who demonstrated erratic behavior and expressed resistance to sexual coercion by European colonizers. Now, however, this phenomenon is widely understood to be a normal reaction to colonial force and rape (Dick, 1995; Fulk, 2012).

Bearing in mind psychiatry’s misogynist, ablest, colonial, racist, homophobic, and classist foundations, many continue to look critically at modern-day approaches to helping individuals in distress and work hard to link psychiatry to other human rights-based movements that seek to explore “the agency and oppression” of those who are suffering (Menzies et al., 2014, p. 1).

New frameworks: medical vs biopsychosocial understandings

A key part of critiquing the status quo and re-framing approaches to understanding the nuances of mental health has been a move away from what has traditionally been called the “medical” model which views mental health issues primarily as individual biological conditions that require diagnosis and treatment by healthcare professionals. The underlying assumption is that if one is unable to participate “productively” in society, they may need to seek help in the form of medication and/or therapy until they can function adequately again.

In contrast, the biopsychosocial model looks beyond one’s biology and instead considers the interplay between genetic predispositions, individual psychological states, and socio-environmental influences. It emphasizes the role of societal structures and cultural norms in contributing to mental health struggles, and advocates for changes in policy, community support, and social inclusion as key strategies for improving mental health outcomes. For example, if you notice a change in behaviour from a student in your class–let’s say they started off the semester strong, but now are struggling to find the energy to come to class and they admit to you that they don’t have the confidence to complete assignments etc., their feelings of depression may be bio-medical in origin, but they might just as likely be brought on by a lack of sleep, or insecure housing arrangements, or a complicated relationship with a family member, friend, or romantic partner. Mahapatra and Sharma (2024) emphasize that this model fosters therapeutic relationships by acknowledging an individual’s lived experiences and their active role in finding helpful coping strategies. Mental health struggles also often occur when an individual undergoes a major life transition: like starting post-secondary studies.

The Prevalence of Mental Health Issues Amongst Post-Secondary Students

Mental health challenges amongst post-secondary students are alarmingly common. A study published in BMC Public Health in 2023 found that over a third of post-secondary students reported a formal mental health diagnosis, with depression and generalized anxiety disorder being the most prevalent (Moghimi et al., 2023). The study highlighted that 60.5% of students felt they did not have good mental health, and 62.4% believed they had inadequate coping strategies. While the distress students are feeling is real, it’s also important to zoom out and not focus solely on the individual but also to look at the broader systems and factors in place that might be contributing to these mental health struggles. That is to say, this research doesn’t claim that young people today are especially prone to depression and anxiety, but rather, given these high numbers, we’d be wise to look at what else is going on in their lives that might result in these distressful feelings. At Conestoga, for example, students cite their primary stressor to be finances, followed by managing course workloads, and trying to balance work and school (OCSES,2022).

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

One important factor to consider is how the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the mental health of post-secondary students. A meta-analysis published in Frontiers in Psychiatry in 2021 revealed that the global prevalence of clinically significant depression and anxiety among post-secondary students during the pandemic was 30.6% and 28.2%, respectively (Zhu, 2021). The pandemic-induced disruptions, including school closures, academic uncertainties, and social isolation, have exacerbated existing mental health issues and introduced new stressors for students.

What can you do to help?

If you encounter a student who seems to be experiencing mental health struggles, you can show them compassion and concern and try to start a conversation (in person or on Zoom or Teams) before deciding whether or not it’s appropriate to refer them to other college resources. Bearing in mind the biopsychosocial model, and maintaining respect for student privacy, it might feel right to ask the student a few more details about what they are going through. This could help you determine the most appropriate supports. For example, if it turns out their anxiety and stress is mostly a result of struggling to stay on top of their course assignments, then it may be most appropriate to first refer them to a student success advisor. If their suffering is largely a result of feeling isolated in a new country and struggling with acculturative stress, then booking an appointment with an International Transition Coordinator might be the best place to start.

You may also want to familiarize yourself with ideas shared in this hub post; it provides suggested conversation starters and additional resources you may find helpful.

Many students may also benefit from support from the Accessible Learning Office or Counselling Services, of course. But, bearing in mind the problematic historic psychiatric practices noted above, it’s important to remember that some students may not want to seek formal treatment or receive a formal mental health diagnosis. For example, there may be cultural stigmas at play, or they may fear that a diagnosis may have negative repercussions on their careers in future.

When in doubt about where to refer a student, the CARE Team is always a great place to go. Refer students to the Conestoga CARE Team by filling in the CARE Team Report form together, with the student present, or on behalf of the student, after they agree to seek further supports and services. The CARE team will then reach out to the student to gather more information before determinig next steps.

References

Dick, L. (1995). “Pibloktoq” (Arctic Hysteria): A Construction of European-Inuit Relations? Arctic Anthropology, 32(2), 1-42

Hogan, A. J. (2019). Social and medical models of disability and mental health: evolution and renewal. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 191(1). p. 16-18. Retrieved from: https://www.cmaj.ca/content/191/1/E16

Fulk M. (2012) Pibloktoq. In: Loue S., Sajatovic M. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of immigrant health. New York, NY: Springer.

Mahapatra, A., Sharma, P. (2024). Biopsychosocial Approach to Mental Health. In: Anand, M. (eds) Mental Health Care Resource Book. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-1203-8_5

Moghimi, E., Stephenson, C., Gutierrez, G., Jagayat, J., Layzell, G., Patel, C., McCart, A., Gibney, C., Langstaff, C., Ayonrinde, O., Khalid-Khan, S., Milev, R., Snelgrove-Clarke, E., Soares, C., Omrani, M., & Alavi, N. (2023). Mental health challenges, treatment experiences, and care needs of post-secondary students: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health. Retrieved from BMC Public Health

Ontario College Student Exprience Survey (2022). Conestoga College.

Ogrodniczuk JS, Kealy D, Laverdière O. (2021). Who is coming through the door? A national survey of self-reported problems among post-secondary school students who have attended campus mental health services in Canada. Couns Psychother Res., 21(4):837–845. doi: 10.1002/capr.12439.

Tasca, C., Rapetti, M., Carta, M. G., & Fadda, B. (2012). Women and hysteria in the history of mental health. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health : CP & EMH, 8, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901208010110

World Mental Health Day 2024 “Mental Health at Work”,

Zhu, J., Racine, N., Xie, E. B., Park, J., Watt, J., Eirich, R., Dobson, K., & Madigan, S. (2021). Post-secondary student mental health during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry. Retrieved from Frontiers in Psychiatry